Adult-adult social play in captive chimpanzees: is it indicative of positive animal welfare?

Yumi Yamanashi, Etsuko Nogami, Migaku Teramoto, Naruki Morimura, Satoshi Hirata

DOI: 10.1016/j.applanim.2017.10.006

This is the self-archived version of the following article: Yamanashi, Y., Nogami, E., Teramoto, M., Morimura, N., & Hirata, S.(2017)Adult-adult social play in captive chimpanzees: is it indicative of positive animal welfare? Applied Animal Behaviour Science , 199: 75-83, which has been published in final form at

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2017.10.006

Abstract

Play is sometimes considered as an indicator of positive animal welfare. However, it is not yet sufficiently understood whether or not social play among adults can be considered as such an indicator because it is rare in adult animals. This study investigates the factors that influence social play in adult captive chimpanzees in order to discuss its function and use as a welfare indicator. The subjects were 37 adult chimpanzees (17 males and 20 females) living in Kumamoto Sanctuary, Kyoto University, Japan. We completed 367 h of behavioural observation of mixed-sex and all-male groups of chimpanzees between June and July 2014, and December 2014 and March 2015, respectively. We collected data on social play, social grooming (mutual and unilateral grooming), aggressive interactions, self-directed behaviours and abnormal behaviours. We checked the relationship between social play and age, sex, timing, social group formation and different social behaviours. The results reveal that social play increased in males of all-male groups compared to those of mixed-sex groups. Furthermore, we analysed behaviours in individuals from all-male groups and found that social play increased before feeding. In addition, although mutual social grooming showed a negative correlation with aggressive interactions, social play did not show such a relationship. Furthermore, social play and mutual social grooming were negatively correlated. These results suggest that social play may be used as a means to reduce social tension and that it does not necessarily indicate that the individuals formed affiliative social relationships such as mutual social grooming indicates. Therefore, although social play is important to enable the coexistence of multiple adult males who do not always get along well, we need to be cautious when interpreting social play from the view of animal welfare.

1. Introduction

How individuals form social relationships with others is important for the welfare of both human and non-human animals. Studies have shown that close bonds increase the survival rate of infants and lead to longevity (Silk

et al., 2003, Silk et al., 2010). A recent study of wild chimpanzees in Budongo forest, Uganda, found that grooming with bonding partners can have a stress reducing effect, as observed in the reduction of the urinary glucocorticoids level after grooming (Wittig

et al., 2016). However, social relationships can sometimes have an opposite effect on animal welfare. Increasing social stress is one obvious example. Studies have reported an increase of physiological stress indicators after aggression and with increasing group size in wild chimpanzees (Markham

et al., 2013, Wittig et al., 2015). Our previous studies showed that the hair cortisol level (as a

physiological index of long-term stress) was higher in captive chimpanzees who received a higher

level of aggression, suggesting that social situation affected their stress levels over long periods

(Yamanashi et al., 2013, Yamanashi et al., 2016a). In wild populations of primates, animals have

various tactics to reduce the costs of group living. One of these is fission. Another coping

strategy is reducing tension and the risk of aggression by engaging in certain affiliative

behaviours, such as social grooming and play. Especially in captive situations, where there is not

much space for fission, coping by means of this active strategy is important. It has been observed

that primates avoid aggression by engaging in affiliative behaviours. Studies have shown that the

affiliative behaviours among great apes increased in spatial crowding situations (de Waal, 1989,

Nieuwenhuijsen and de Waal, 1982, Ross et al., 2010, Videan and Fritz, 2007).

There are several types of affiliative social behaviours.

Among those, social grooming is the most ubiquitous form of affiliative behaviour. Social grooming

is considered to be used as a means to establish and maintain social bonds as well as to maintain

hygiene. Studies have shown a correlation between grooming interchange and support for agonistic

interactions in captive chimpanzees (Hemelrijk and Ek, 1991). Mitani (2009) reported that grooming

reciprocity occurred between maternal brothers and dyads with strong social bonds. Studies of other

primates likewise reported a link between social grooming and affiliative relationships, such as

close kin, bond duration and co-feeding (Silk et al., 2006, Ventura et al., 2006). However, compared

to the wealth of knowledge concerning social grooming, studies of social play, especially among

adults, are scarce. This is because adult–adult social play is rare in non-human animals. For

example, Matsusaka (2004) reported that, in a study of wild chimpanzees in Mahale Mountain National Park, Tanzania, only 12 out of 793 bouts of social play occurred between adults, whereas the other 781 bouts occurred including immature individuals. Although many previous studies classify social play and social grooming in the same category of affiliative behaviours, it is not clear whether these two behaviours can be considered identical. It is known that bonobos, a species that is closely related to chimpanzees, are more playful than chimpanzees. Palagi

(2006) reported that the rate of social play of adult bonobos increased before feeding rather than

control periods. Additionally, Palagi (2006) found that the rate of social play and co-feeding was

positively correlated. Tension among group members can be high during the pre-feeding period due to

the anticipation for food. Therefore, she concluded that social play between adult bonobos is

related to reduce tension between affiliative pairs and hence to reduce aggression. However, the

social traits of chimpanzees and bonobos are very different (Hare et al., 2012), and some studies of

other mammals failed to find a relation between affiliative relationships and social play (Cordoni,

2009, Sharpe, 2005, Sharpe and Cherry, 2003). Therefore, it is important to understand the details

of social play among adults and its relevance to other social behaviours.

Understanding what type of social relationship social play

reflects is also important from the perspective of animal welfare assessment. Attention for positive

animal welfare has been increasing, and play is sometimes considered as a positive indicator of

welfare (Boissy et al., 2007, Held and Špinka, 2011). This is because play is often observed when

animals are without chronic stress (Graham and Burghardt, 2010) and is often accompanied by signs of

pleasure (Held and Špinka, 2011). In addition to such immediate benefits, play also has delayed

benefits and is important for the socio-cognitive development of immature animals (Shimada and

Sueur, 2014). A recent study showed that social play during juvenile periods correlated with future copulation behaviours in American minks (Ahloy

Dallaire and Mason, 2017). Locomotor play facilitates motor skill acquisition in Assamese macaques

(Berghänel et al., 2015). Therefore, increasing the level of play among immature animals can be

important from the perspective of animal welfare. Nevertheless, it is controversial whether play,

especially social play, which is the most prevalent form of play after maturation (Pellis and

Iwaniuk, 2000), can be considered as a positive indicator of welfare (Blois-Heulin et al., 2015).

Age, sex and species differences are often associated with the level of social play (Burghardt,

2005). In addition, social play of adult non-human primates is also frequent in contexts of

heightened tension, such as pre-feeding time for bonobos (Palagi et al., 2006) and in contexts of

group encounter for Verreaux’s sifaka (Antonacci et al., 2010). Furthermore, the above-mentioned

study of immature Assamese macaques (Berghänel et al., 2015) also reported a negative correlation

between physical development and locomotor play rate, which suggests energy-demanding aspects of

play. Therefore, it is under debate how we should deal with social play from the perspective of

animal welfare.

This study investigates the factors that influence social

play in adult captive chimpanzees by using unique captive settings to discuss the function of social

play. First, we describe the influence of age, sex and group formation on social play levels in

chimpanzees living in mixed-sex and all-male groups. Then, we investigate the time distribution of

social behaviours, the association among three social behaviours (social play, social grooming and

aggressive interaction) in all-male groups of chimpanzees. We also examined the association between

social play and abnormal and self-directed behaviours because these behaviours have been frequently

used as indicators of animal welfare (Baker and Aureli, 1997, Duncan and Fraser, 1997). If social

play used as a means to reduce social tensions among individuals, social play among adult

chimpanzees can increase during times of heightened tension, such as pre-feeding time. Furthermore,

we predicted that social play is higher in males than in females and can be increased in all-male

groups with many adult males coexisting in a closed environment. If social play can be considered as

a means to form and maintain social bond, social play can be an indicative of affiliative

relationships similar to how mutual grooming was observed to be (Fedurek and Dunbar, 2009). We

predicted that social play can be observed between dyads of affiliative social relationships with

high levels of social grooming and low levels of aggressive interaction. Based on these findings, we

will discuss the use of social play as an indicator of positive welfare.

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects and

housing

2.2. Data collection

2.3. Data analysis

2.3.1. Sex, age and group differences affecting social play

2.3.2. Timing of social behaviours and relationship between social play, aggressive interactions and social grooming

2.4. Statistical analysis

2.4.1. Sex, age and group difference of social play

2.4.2. Timing of social behaviours and relationship between social play, aggressive interactions and social grooming

The subjects are 37 adult chimpanzees (17 males and 20 females) living in

Kumamoto Sanctuary, Wildlife Research Center, Kyoto University (KS). The subjects were

divided into several social groups which include both all-male groups and mixed-sex groups

(Table 1). In the case of males, we collected data from 11 all-male group chimpanzees and

six mixed-sex chimpanzees. Two out of five mixed-sex groups have two males, while other

groups have only one male in a group. However, one male from a mixed-sex group with two

males moved to another zoo for breeding during the study (September 2014). Therefore, only

data from the six males in the mixed-sex group was included. Three to six females lived with

those males. The members of the all-male groups changed periodically as described in the

Supplementary Table. All individuals were above nine years old, and the details of their

profiles and social structures are supplied in the Supplementary 1. Males in the all-male

groups of chimpanzees were biologically unrelated except for one dyad that had an

uncle-nephew relationship.

Established in 2007, KS was the first chimpanzee

sanctuary in Japan (it was renamed from Chimpanzee Sanctuary Uto (CSU) in 2011 when the

institution was passed from Sanwa Kagaku Research Institute onto Kyoto University). For more

information, see (Morimura et al., 2010). KS accommodates ex-laboratory chimpanzees and chimpanzees that are considered surplus in Japanese zoos. It promotes the social life of chimpanzees. Three types of social groups have formed within KS: all-male groups; one-male and multi-female groups; and multi-male, multi-female groups. The members of the all-male groups are changed periodically to provide social stimulation and prevent escalated aggression, especially directed toward immigrant individuals. All individuals had access to both indoor and outdoor enclosures, most of which are cage style (i.e.

a building with a roof), although one outdoor enclosure (approximately 270 m2 in

area) has no roof. The outdoor cages range in size from approximately 70 m2 in

area and 5.4 m in height to about 120 m2 in area and 12 m in height.

All these outdoor cages are connected to other cages. During wintertime, some of the outdoor

cages were covered with plastic sheeting so that the chimpanzees could avoid cold temperatures.

Passages that connect several cages within KS were introduced, totalling 150 m in length, and groups of chimpanzees could access these passages for exploration in turn. They had free access to water at any time, and regular meals (consisting mainly of fruit, vegetables and monkey pellets) were provided three times per day. Additionally, routine feeding enrichment (e.g. juice feeders, puzzle feeders, browsing opportunities and food concealed in boxes or newspapers) were changed daily. Other types of environmental enrichment were also provided. For example, fire hoses, ropes, hammocks, climbing structures, and substrate materials were installed and natural vegetation was planted to increase the physical environment’s complexity. Moreover, spaces were available for the chimpanzees to escape from rain, strong sunlight and cold, and they were provided with comfortable bedding materials for day- and night-time sleep. Materials that they could manipulate freely were also provided, such as toys, buoys and sacks. For additional details on environmental enrichment, see (Kumamoto

Sanctuary). In addition to the lifelong care of these chimpanzees and bonobos, non-invasive research (cognitive, behavioural, endocrinological and genetic) is conducted at KS (Kano

et al., 2015, Krupenye et al., 2016, Morimura and Mori, 2010, Yamanashi et al., 2016a, Yamanashi

et al., 2016b).

2.2. Data collection

Data were collected between June and July 2014 (summer), and between December

2014 and March 2015 (winter), respectively. The total observation time was 367 h (229 h

for the all-male groups and 138 h for the mixed-sex groups). All data were collected by

YY, using the iOS application “ISBOapp” (Ogura, 2013) and a notebook to complement. Table 2

shows details of the social play patterns and definitions of behaviours. The definitions

were based on Palagi and Paoli (2007), Goodall (1989), Baker and Aureli (1997), Birkett and

Newton-Fisher (2011), Walsh et al. (1982) and Nishida et al. (2010). Between 9:00 h and

16:00 h, YY conducted 30 min of focal observation of 17 male chimpanzees in a

randomly assigned order and recorded behaviours of the chimpanzees in their enclosures

(Martin and Bateson, 2007). At least 20 h (20–21 h in all-male groups and

21.5–24.5 h in mixed-sex groups) of focal animal sampling were conducted for each male

individual. During the observations, YY recorded social grooming, social play, self-directed

behaviours, abnormal behaviours and other general behaviours (forage, rest, move, and other

behaviours, not used for this study) every 30 s and all aggressive interactions and

social play that occurred within the groups. Although we tried to quantify the ranks of the

individuals by the direction of pant grunting (Nishida et al., 2010, Noe et al., 1980), we

could identify only the two highest- and two lowest-ranking individuals (Yamanashi et al.,

under review). The group members directed pant grunts toward the alpha male, and the

lowest-ranking individuals directed pant grunts toward several individuals. However, there

were many blank relationships and other individuals did not pant-grunt at each other. Thus,

we were unable to quantify the rank of every individual. YY stopped making focal

observations and began recording aggressive interactions when a scream or play sound was

heard or when there were any other signs of aggression or social play. YY recorded the

aggressors and receivers of each aggressive interaction. To record social play, YY checked

whether the same dyads continued social play 30 s after first noticing the start of the

play and repeated to check after every 30 s until YY saw that the chimpanzees did not

engage in social play at all, as social play often continued for relatively a long period.

We considered the observed behaviours as two separate bouts if no social play was seen for

the duration of two recording times and it started again from the next recording time.

Social play seldom occurred in mixed-sex groups, hence it was often missed by the

time-sampling approach. To compensate for this difficulty, we collected the social play data

in two different ways (focal animal sampling and all-occurrence sampling), and as a result

we were able to compare the rate of play both within and across groups and sexes. In order

to check the validity of the data collected, we checked the matrix correlation between the

social play data obtained by means of focal sampling and the data obtained by means of

all-occurrence sampling in the all-male groups (11 males). We obtained a significant

correlation between the two data sets (Goodman–Kruskal gamma = 0.800, p < 0.001,

UCINET 6). All the data were collected by a single observer, therefore running the risk of

some social play observations being overlooked. Nevertheless, this positive correlation

implies that our observations were valid.

Between the all-male groups and mixed-sex groups,

several differences were observed in husbandry routine in addition to group formation. Before

11:00 h every morning, 11 all-male group chimpanzees were divided into smaller groups that

consisted of two to three individuals. At approximately 11:00 h, food was scattered in the

enclosures and two social groups that consisted of four to seven individuals were formed until

15:00 h. The groups were fed evening meals and separated again into small social groups

after 15:00 h. The members of each small social unit were changed daily. Data was collected

between 11:00 h and 15:00 h, therefore observed behaviours from the all-male groups

were recorded when the chimpanzees were divided into two social groups. The mixed-sex groups

were also separated into smaller groups (one–seven individuals per group) during the night.

Larger social groups, which consisted of all members of each social group, were formed in the

morning. At approximately 13:00 h, food was scattered in the enclosures, and sometimes the

enclosures used by each group would be changed afterwards. The groups were fed evening meals at

approximately 15:30 h–16:00 h and separated again into small groups afterwards. The data

were collected between 9:00 h and 16:00 h for the mixed-sex groups.

2.3. Data analysis

2.3.1. Sex, age and group differences affecting social play

To analyse the effects of sex, age and group

compositions on the level of social play, we used the data obtained from all-male and

mixed-sex groups. To check the effects of sex on the occurrence of social play, we

calculated the expected value for the occurrence of social play for each sex combination

(male-male, male-female and female-female). The expected value was calculated by dividing

the number of play occurrences by the number of possible sex combinations.

2.3.2. Timing of social behaviours and relationship between social play, aggressive interactions and social grooming

We focused on the all-male groups to analyse the

timing of social behaviours and the relationship amongst three social behaviours. This was

done because a sufficient amount of social play data from all-male group chimpanzees was

obtained. We divided social grooming into two categories (mutual social grooming and

unilateral social grooming) for analysis (Nishida et al., 2010). This is because previous

studies often considered mutual grooming to be an indicator of a strong social bond, as

mutual grooming requires both individuals’ active engagement in the behaviour (Fedurek and

Dunbar, 2009), while unilateral grooming does not. We considered the differences and

analysed each behaviour separately.

We used grooming equality index and the rate of

mutual social grooming to check the relationship among social behaviours (social play,

aggressive interactions and social grooming). Grooming equality index was calculated based

on Mitani (2009) as follows;

where

Gab is the amount of grooming that individual a gave to individual b, Gba is the amount of

grooming that individual b gave to individual a, and Ga ⇔ Gb is the total amount

of grooming between individual a and b. This measure’s strength lies in quantifying whether

grooming between pairs of chimpanzees was balanced or skewed. Therefore, the lower the

index, the more the direction of unilateral social grooming was skewed without

reciprocation. The index ranges from 0 to 1. Further, we also used the rate of mutual

grooming because the chimpanzees in our subject spent considerable time for mutual grooming

and the grooming equality index overlook the level of mutual social grooming between pairs

of animals. The dyad level rate of mutual grooming was calculated by summing the rate of

mutual grooming in each individual focal time. The dyad-level rate of social interactions

was used because we wanted to investigate the type of social relationship the social play

implies.

We calculated one social matrix for each social

behaviour by calculating the sum of the social interactions for each dyad. Because the group

formation changed daily in the all-male groups, we adjusted the social matrices using the

rate of the same groups by dividing the matrices by the total number of observational

sessions of the same group. Missing values were accounted for using statistical procedures

described in the next section. We did not discuss the relationship between individual rates

of social behaviours because these rates can be affected by factors such as group size and

individual situations. Instead, we focussed on the quality of relationship in this study.

2.4. Statistical analysis

2.4.1. Sex, age and group difference of social play

We used Spearman’s rank correlation test to check

the relationship between age and level of play. We analysed the effects of age separately

for all-male group males, mixed-sex group males and females because the absolute levels of

play differ significantly between group and sex (data shown in the result section). We used

the ‘coin’ package to perform Spearman’s rank correlation test (Hothorn et al., 2006,

Hothorn et al., 2008). We used a proportion test to test the differences in the number of

social play and aggressive interactions among the different groups. We used Generalized

Linear Mixed Model (GLMM) to test the differences in the rate of social play and social

grooming between the different groups. To test the effects of the group, we included group

ID as explanatory factor. We also included individual ID and season (summer or winter) as

random factors, as there was substantial difference in the absolute level of play between

different seasons (i.e. they played less in summer). We used the glmer

function of the ‘lme4’ package and gamma distribution with inverse link function.

2.4.2. Timing of social behaviours and relationship between social play, aggressive interactions and social grooming

To test the effects of the time of day on the rate

of social grooming and social play, we used a Generalized Linear Model. We included eight

time-categories (periods of 30 min between 11:00 h and 15:00 h) and

individual ID as explanatory factors. We subsequently used the glm function and

gamma distribution with inverse link function. We did not use GLMM to avoid convergent

errors. We compared the models with and without the explanatory parameters mentioned above

based on the likelihood ratio test with approximate chi-squared distribution (Kubo, 2012).

We conducted a test for equality of proportion to assess the differences in the frequency of

aggressive interaction and social play across the day. Subsequently, we also conducted

post-hoc pairwise comparison of proportions and p values were adjusted with the holm

methods. We used a partial Kr matrix correlation tests to analyse the relationship between

social behaviours (grooming, play and aggressive interactions). The socio-matrixes missed

certain values, as two individuals had never been together with three individuals.

Therefore, we used a partial Kr test to account for the missing values while using all

available data (Hemelrijk, 1990a). The number of permutation was set at 10000. We further

examined the correlation between social play and abnormal and self-directed behaviours using

Spearman’s rank test. All statistical testing was conducted with R. 3.4.1 (R Development

Core Team, 2011), except for the partial Kr test, which was analysed using a special ad-in

created by Hemelrijk and downloaded through her website (Hemelrijk, 1990a, Hemelrijk,

1990b). The level of significance was set at α = 0.05 and we considered it to be

marginally significant when 0.05 < α < 0.1.

3. Results

3.1. Sex, age and

group differences of social play in sanctuary living chimpanzees

3.2. Timing of social behaviours in all-male group chimpanzees

3.3. Relationship between social play, aggressive interactions and social grooming in all-male group chimpanzees

3.4. Relationship between social play and abnormal and self-directed behaviours in all-male group chimpanzees

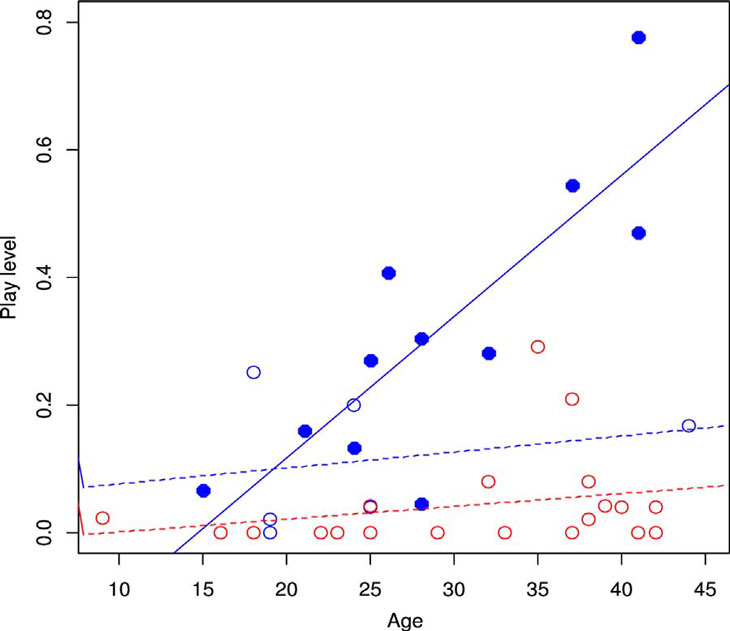

We found a significant positive correlation between age and rate of play in

all-male group chimpanzees (Fig. 1: Z = 2.40, n = 11, p = 0.0165).

We did not find such a correlation in mixed-sex males (Z = −0.130, n = 6,

p = 0.897) or females (Z = 1.15, n = 21, p = 0.251).

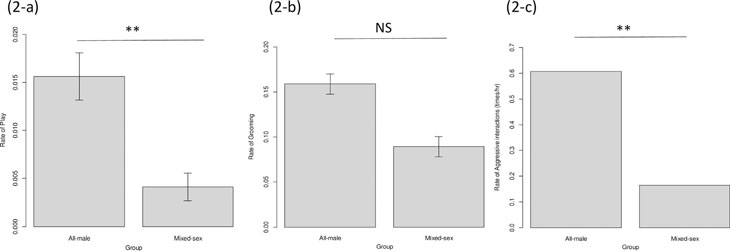

Overall, social play increased in chimpanzees of all-male groups. The rate of play was

higher in all-male groups, as we observed only 29 play bouts in mixed-sex groups during 138 h

of observation, while we observed 384 play bouts during 229 h of observation of the

all-male groups (χ2 = 166.4, df = 1, p < 0.001).

We obtained the same results from comparisons with social play data obtained from focal

animal sampling of male chimpanzees and found that the rate of social play was higher in

all-male groups (Fig. 2-a: est. = 59.5, SE = 2.60, t = 22.9, p < 0.001).

We also found that the rate of aggressive interactions was higher in all-male groups, as we

observed only 25 aggression bouts in mixed-sex groups during 138 h of observation while

151 aggression bouts were observed in all-male groups during 229 h of observation (Fig.

2-c: χ2 = 40.4, df = 1, p < 0.001). We did not

find significant differences in social grooming rate (including both mutual and unilateral

social grooming) between male chimpanzees from mixed-sex and all-male groups (Fig. 2-b: est. = 1.63,

SE = 1.59, t = 1.03, p = 0.305) (Fig. 2).

Among the 29 play bouts observed in mixed-sex groups, 22 play bouts were

between males and females. Only 6 play bouts were between females (Table 3).

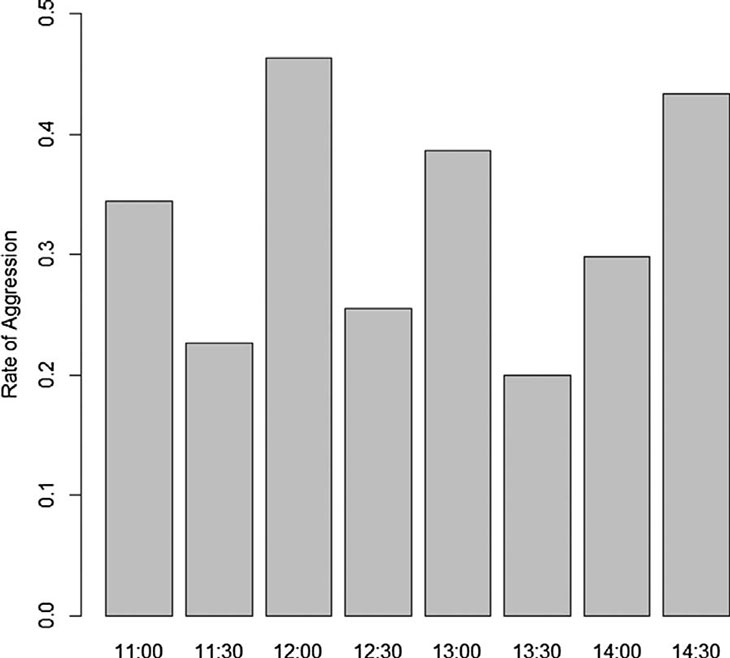

3.2. Timing of social behaviours in all-male group chimpanzees

The distribution of unilateral social grooming and social play across the day

showed similar patterns. Both behaviours increased toward the middle of the day, dropped

once in the early afternoon and increased again toward pre-feeding time (Table 4; unilateral

social grooming: likelihood ratio test, ΔD = 16.9, p = 0.0159; social

play: likelihood ratio test, ΔD = 41,7, p = 0.0452). However, we did not

find significant variation in mutual social grooming across the day (Table 4; likelihood

ratio test, ΔD = 20.9, p = 0.235). Social play was also significant when

we tested the differences in the number of social play bouts across the day (χ2 = 71.0,

df = 7, p < 0.001). In addition to pre-feeding time, we found another

peak in the middle of the day. The results of the post-hoc pairwise comparisons were shown

in Supplementary 2. Aggressive interactions varied significantly across the day (Fig. 3:

χ2 = 15.3, df = 7, p = 0.0318), but post-hoc test

did not find any significant difference in any pairwise comparison (Supplementary 2, p > 0.43).

The frequency of aggressive interactions was relatively higher during pre-feeding time,

although the peak of aggressive interactions was also observed between12:00 h and 12:30 h.

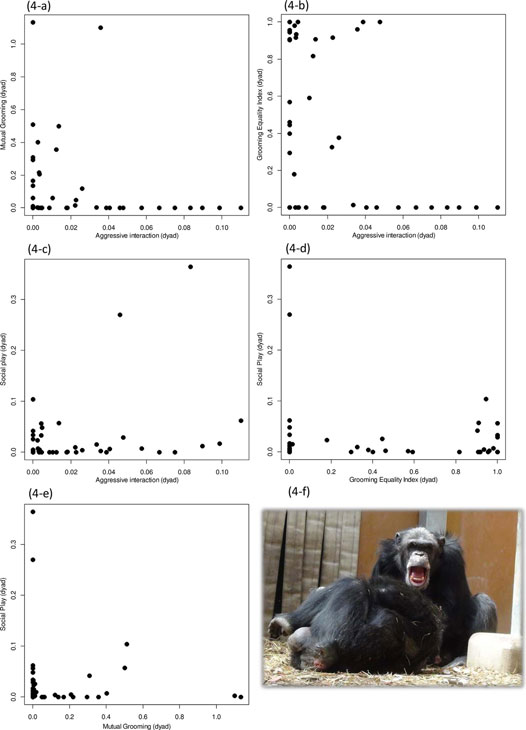

3.3. Relationship between social play, aggressive interactions and social grooming in all-male group chimpanzees

There was a negative correlation between the rate of aggressive interactions

and mutual grooming (Fig. 4-a: τKr = −0.70, p = 0.0002), and

a similar trend was found between aggressive interactions and grooming equality index (Fig.

4-b: τKr = −0.18, p = 0.061). There was no correlation

between the rate of aggressive interactions and social play (Fig. 4-c: τKr = −0.095,

p = 0.25), and grooming equality index and social play (Fig. 4-d: τKr = −0.11,

p = 0.18). The rate of mutual social grooming and social play showed a negative

relationship (Fig. 4-e: τKr = −0.45, p = 0.0035). In a few

cases, social play (Fig. 4-f) itself lead to aggressive interactions (6 out of 151

aggression bouts).

3.4. Relationship between social play and abnormal and self-directed behaviours in all-male group chimpanzees

There was no significant correlation between social play

and abnormal behaviour (Z = 1.06, n = 11, p = 0.288), and between

social play and self-directed behaviour (Z = −0.144, n = 11, p = 0.886).

4. Discussion

4.1. Sex, age,

timing and group differences of social play

4.2. Social play and relationship quality

4.3. Social play and tension reduction

4.4. Social play and animal welfare assessment

4.5. Limitation and future perspectives

Social play increased in all-male group chimpanzees

compared to those in mixed-sex groups with fewer males. Males are more playful than females, as

most play bouts included at least one male. Females seldom engaged in social play without males,

despite the fact that there were many females among our subjects. Previous studies on sex

differences in immature chimpanzees (Lonsdorf et al., 2014, Mendoza-Granados and Sommer, 1995)

and other mammals (Pellis, 2002) similarly reported that males are more playful than females.

Our study reveals that this sex difference is consistent in adulthood.

Additionally, consistent with previous studies of

chimpanzees and bonobos (Palagi, 2006, Palagi et al., 2004), social play and unilateral social

grooming increased before feeding, when tension is heightened. There seems to be a similar

rhythm of behaviours in both unilateral social play and social grooming. They increased toward

the middle of the day, decreased once and then increased again toward pre-feeding time. The

reason why social play and grooming increased in the middle of the day may be because the

caregivers always came to check the chimpanzees and provided enrichment between 13:00 h and

14:00 h. Aggressive interactions occurred across the day, but it slightly increased before

feeding. Although social play and unilateral social grooming showed similar patterns, the

variation of mutual social grooming across the day was not significant and the peak of mutual

social grooming occurred earlier than that of unilateral social grooming and social play.

Considering that the peak of unilateral social grooming, social play and aggressive interactions

occurred during pre-feeding time, mutual social grooming may have a different function.

Interestingly, the individual rate of social play

increased with age in all-male group chimpanzees. Some suggest that the rate of play decreases

according to age (Graham and Burghardt, 2010) but these studies often include subjects with ages

occurring from infancy to adolescence (Bloomsmith et al., 1994). Our study is unique because it

included individuals after the adolescent stage, between the ages of 9 and 44. More data is

needed to support this finding, but it is possible that older chimpanzees may use social play as

a tactic to reduce social tensions.

4.2. Social play and relationship quality

Although the time distribution was similar for

unilateral social grooming and social play, mutual social grooming and social play imply totally

different social relationships. Mutual social grooming reflected an affiliative relationship, as

there was a negative relationship with aggressive interactions. The finding of an association

between mutual social grooming and affiliative relationships is consistent with studies of

another captive group of chimpanzees, which demonstrated a correlation between the rate of

mutual social grooming and proximity and reported that dyads with kin relationship engaged in

mutual social grooming more frequently than those without such a relationship (Fedurek and

Dunbar, 2009). Such a negative relationship with aggressive interactions was also observed in

grooming equality index, but it was weaker than in the rate of mutual grooming. Chimpanzees

spent considerable time in mutual grooming. Machanda et al. (2014) did not find significant

relationship between mutual grooming and association index, but they found that individuals who

avoided each other were less likely to engage in mutual grooming. This means that wild

chimpanzees can use “fission” strategy to avoid individuals with a low relationship quality. In

captive conditions, chimpanzees often have to tolerate such individuals in the same enclosure.

Such situation might influence the differences in the results of the studies conducted in wild

and captive conditions.

However, social play occurred not only between dyads

without aggressive interactions, but also between those with aggressive interactions.

Furthermore, mutual social grooming and social play showed a negative correlation. Therefore,

mutual social grooming implies an affiliative relationship, but that is not always the case for

social play. We can distinguish social play from other behaviours, namely, as behaviours

including play panting or play laughing. Such pleasurable experiences may decrease the threshold

of social interactions even among dyads with a low relationship quality.

4.3. Social play and tension reduction

Social play increased before feeding, also in all-male

groups. Both situations can be related to heightened social tension as we observed increased

aggressive interactions in both situations. In our previous study, we found that the hair

cortisol level was lower in males from the all-male groups than in those from mixed-sex groups.

Combined with the present findings, males in the all-male groups may use social play as a means

to cope with social tensions, especially among conspecifics with a low-quality relationship.

Social play may not necessarily facilitate close bonding because it has a negative correlation

with mutual social grooming in the already established groups. However, individuals with a

low-quality relationship might assess and tolerate each other by engaging in social play.

Therefore, social play is important for the coexistence of several males who do not always get

along well.

Interestingly, bonobos are more playful than

chimpanzees, and they are also less aggressive and more cohesive than chimpanzees (Hare and

Yamamoto, 2015). Hare et al. (2012) proposed the hypothesis that self-domestication occurs in

bonobos, because the above-mentioned traits of bonobos are similar to those of animals selected

by means of artificial selection. Adult chimpanzees were considered to play less, but our study

revealed that this also depends on their environment. We observed the increase of social play in

the captive environment lacking fitness threat, but socially closed environment with several

unrelated males. Therefore, understanding the social play of adult chimpanzees living in various

captive social environments may provide more clues for how certain traits of humans and bonobos

evolved.

4.4. Social play and animal welfare assessment

Our study’s findings question the view that social play can be used as an indicator of positive animal welfare. Although we need more discussion on what is “positive” animal welfare, basically positive states can be related to relaxed states without fitness threat. Additionally, it should accompany good social relationships, as our previous studies reported the importance of social relationships for the long-term stress levels of captive chimpanzees (Yamanashi

et al., 2013, Yamanashi et al., 2016a). The fact that social play increased with increasing age

in all-male groups, sex and group differences and time of social play, correlation with other

social behaviours, and absence of correlation with self-directed and abnormal behaviours,

indicate the complexity of social play. Because social play is important for maintaining social

groups among adult male chimpanzees, it is essential to consider this behaviour in the context

of captive group management. However, it is difficult to assert that individuals maintain good

relationships with each other. Therefore, we did not ascertain that social play is a negative

indicator; instead, the interpretation of the behaviour as animal welfare indicators should be

determined by combining it with other welfare indicators and treating it in a similar manner.

4.5. Limitation and future perspectives

There are some limitations of our study regarding

understanding the social play among adult chimpanzees. Although we found that males in the

all-male groups played and engaged in aggressive behaviours more than those in the mixed-sex

groups, we could not differentiate whether the number of males or other factors in the all-male

groups (e.g. frequent social changes) were responsible for the differences. We did not observe

the same behaviour in the social group, which included several males and females, because it is

rare in a captive environment (Bloomsmith and Baker, 2001). Another point is that although this

study treated social play as one category of behaviour, social play includes behaviours with

different modalities and intensity (Palagi and Paoli, 2007). There might be a difference between

underlying motivation and emotion, depending on such modality differences. Furthermore, although

we did not find evidence that social play deepens the social relationship among individuals,

there is still such a possibility in the case of introduction of new individuals because social

play can have a function of social assessment (Graham and Burghardt, 2010, Pellis and Iwaniuk,

2000). Future studies should investigate social play and its relevance to the internal states in

more diverse types of social groups and in more diverse social situations in depth.

5. Conclusion

To sum up, social play and unilateral social grooming are

similar in terms of the occurring behaviours’ timing. However, social play and mutual grooming were

not similar in terms of the occurring behaviours’ timing and also did not imply a similar social

relationship, as social play does not necessarily indicate an affiliative social relationship in the

same way that mutual social grooming does. Individuals with low relationship quality also engaged in

social play to reduce social tension. Combined with the finding that social play increased in

all-male group chimpanzees, social play is important for the coexistence of multiple adult males who

do not always get along well. Although this is an important behaviour in the context of the social

management and welfare assessment of captive chimpanzees, we have to be cautious when we assess

animal welfare using social play. The notion that all social play implies ‘positive’ welfare is

oversimplified, since individuals do not always have affiliative relationships with others, which is

an important point when considering animal welfare. Therefore, as we treated other welfare

indicators, we need a more holistic view to interpret social play by combining multiple welfare

indicators.

Acknowledgements

The care of the chimpanzees and the present study were supported

financially by grants from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science

(#13J04636 and #17K17828 to YY, #25119008 to SH, #15H0579, #16H06301, #16H06283, JSPS-LGP-U04, JSPS

core-to-core CCSN) and also by Future Development Funding Program of Kyoto University Research

Coordination Alliance and Great Ape Information Network. We are grateful to the following people and

institutions for their support of our study: Yusuke Mori, Toshifumi Udono and the staff at the Kumamoto

Sanctuary. We also thank Masaki Shimada for invaluable discussion regarding this study and Yusuke Hori

and Daisuke Muramatsu for statistical advice.

References

- Ahloy Dallaire, J., Mason, G.J., 2017. Juvenile rough-and-tumble play predicts adult sexual behaviour in American mink. Anim. Behav. 123, 81–89. http://dx.doi.org/10. 1016/j.anbehav.2016.10.023.

- Antonacci, D., Norscia, I., Palagi, E., 2010. Stranger to familiar: wild strepsirhines manage xenophobia by playing. PLoS One 5 (10), e13218. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/ journal.pone.0013218.

- Baker, K.C., Aureli, F., 1997. Behavioural indicators of anxiety: an empirical test in chimpanzees. Behaviour 134, 1031–1050.

- Berghänel, A., Schülke, O., Ostner, J., 2015. Locomotor play drives motor skill acquisition at the expense of growth: a life history trade-off. Sci. Adv. 1 (7). http://dx.doi.org/10. 1126/sciadv.1500451.

- Birkett, L.P., Newton-Fisher, N.E., 2011. How abnormal is the behaviour of captive, zooliving chimpanzees? PLoS One 6 (6), e20101.

- Blois-Heulin, C., Rochais, C., Camus, S., Fureix, C., Lemasson, A., Lunel, C., Hausberger, M., 2015. Animal welfare: could adult play be a false friend? Anim. Behav. Cogn. 2 (2), 156–185.

- Bloomsmith, M., Baker, K.C., 2001. Social management of captive chimpanzees. In: Brent, L. (Ed.), The Care and Management of Captive Chimpanzees. American Society of Primatologists, San Antonio, pp. 205–242.

- Bloomsmith, M., Pazol, K., Alford, P., 1994. Juvenile and adolescent chimpanzee behavioral development in complex groups. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 39 (1), 73–87.

- Boissy, A., Manteuffel, G., Jensen, M.B., Moe, R.O., Spruijt, B., Keeling, L.J., Aubert, A., et al., 2007. Assessment of positive emotions in animals to improve their welfare. Physiol. Behav. 92 (3), 375–397.

- Burghardt, G.M., 2005. The Genesis of Animal Play: Testing the Limits. Mit Press. Cordoni, G., 2009. Social play in captive wolves (Canis lupus): not only an immature affair. Behaviour 146 (10), 1363–1385. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/ 156853909x427722.

- de Waal, F.B.M., 1989. The myth of a simple relation between space and aggression in captive primates. Zoo Biol. 8 (S1), 141–148. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/zoo. 1430080514.

- Duncan, I.J.H., Fraser, D., 1997. Understanding animal welfare. In: Appleby, M., Hughes, B.O. (Eds.), Animal Welfare. CAB International, Wallingford, pp. 19–31.

- Fedurek, P., Dunbar, R.I.M., 2009. What does mutual grooming tell us about why chimpanzees groom? Ethology 115 (6), 566–575. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1439- 0310.2009.01637.x.

- Goodall, J., 1989. Glossary of Chimpanzee Behaviors. Jane Goodall Institute.

- Graham, K.L., Burghardt, G.M., 2010. Current perspectives on the biological study of play: signs of progress. Q. Rev. Biol. 85 (4), 393–418.

- Hare, B., Yamamoto, S., 2015. Moving bonobos off the scientifically endangered list. Behaviour 152 (3–4), 247–258.

- Hare, B., Wobber, V., Wrangham, R., 2012. The self-domestication hypothesis: evolution of bonobo psychology is due to selection against aggression. Anim. Behav. 83 (3), 573–585. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2011.12.007.

- Held, S.D.E., Špinka, M., 2011. Animal play and animal welfare. Anim. Behav. 5 (81), 891–899. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2011.01.007.

- Hemelrijk, C.K., Ek, A., 1991. Reciprocity and interchange of grooming and ‘support’ in captive chimpanzees. Anim. Behav. 41 (6), 923–935. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ S0003-3472(05)80630-X.

- Hemelrijk, C.K., 1990a. A matrix partial correlation test used in investigations of reciprocity and other social interaction patterns at group level. J. Theor. Biol. 143 (3), 405–420. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5193(05)80036-0.

- Hemelrijk, C.K., 1990b. Models of, and tests for, reciprocity, unidirectionality and other social interaction patterns at a group level. Anim. Behav. 39 (6), 1013–1029. http:// dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0003-3472(05)80775-4.

- Hothorn, T., Hornik, K., van de Wiel, M.A., Zeileis, A., 2006. A lego system for conditional inference. Am. Stat. 60 (3), 257–263.

- Hothorn, T., Hornik, K., van de Wiel, M.A., Zeileis, A., 2008. Implementing a class of permutation tests: the coin package. J. Stat. Softw. 28 (8), 1–23.

- Kano, F., Hirata, S., Call, J., 2015. Social attention in the two species of Pan: bonobos make more eye contact than chimpanzees. PLoS One 10 (6), e0129684. http://dx.doi. org/10.1371/journal.pone.0129684.

- Krupenye, C., Kano, F., Hirata, S., Call, J., Tomasello, M., 2016. Great apes anticipate that other individuals will act according to false beliefs. Science 354 (6308), 110–114. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf8110.

- Kubo, T., 2012. Introduction to Statistical Modeling for Data Analysis: Generalized Linear Model, Hierarchical Bayesian Model and MCMC. Iwanami shoten, Tokyo.

- Kumamoto Sanctuary. Retrieved 31st July, 2015, from http://www.wrc.kyoto-u.ac.jp/ kumasan/indexE.html.

- Lonsdorf, E.V., Anderson, K.E., Stanton, M.A., Shender, M., Heintz, M.R., Goodall, J., Murray, C.M., 2014. Boys will be boys: sex differences in wild infant chimpanzee social interactions. Anim. Behav. 88, 79–83. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav. 2013.11.015.

- Machanda, Z.P., Gilby, I.C., Wrangham, R.W., 2014. Mutual grooming among adult male chimpanzees: the immediate investment hypothesis. Anim. Behav. 87 (0), 165–174. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2013.10.028.

- Markham, A.C., Santymire, R.M., Lonsdorf, E.V., Heintz, M.R., Lipende, I., Murray, C.M., 2013. Rank effects on social stress in lactating chimpanzees. Anim. Behav. 0. http:// dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2013.10.031.

- Martin, P., Bateson, P., 2007. Measuring Behaviours: An Introductory Guide, 3rd ed. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Matsusaka, T., 2004. When does play panting occur during social play in wild chimpanzees? Primates 45 (4), 221–229. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10329-004-0090-z. Mendoza-Granados, D., Sommer, V., 1995. Play in chimpanzees of the Arnhem Zoo: selfserving compromises. Primates 36 (1), 57–68. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/ bf02381915.

- Mitani, J.C., 2009. Male chimpanzees form enduring and equitable social bonds. Anim. Behav. 77 (3), 633–640. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2008.11.021.

- Morimura, N., Mori, Y., 2010. Effects of early rearing conditions on problem-solving skill in captive male chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Am. J. Primatol. 72 (7), 626–633. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ajp.20819.

- Morimura, N., Idani, G., Matsuzawa, T., 2010. The first chimpanzee sanctuary in Japan: an attempt to care for the surplus of biomedical research. Am. J. Primatol. 73 (3), 226–232. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ajp.20887.

- Nieuwenhuijsen, K., de Waal, F.B.M., 1982. Effects of spatial crowding on social behavior in a chimpanzee colony. Zoo Biol. 1 (1), 5–28. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/zoo. 1430010103.

- Nishida, T., Zamma, K., Matsusaka, T., Inaba, A., McGrew, W.C., 2010. Chimpanzee Behavior in the Wild: An Audio-visual Encyclopedia. Springer-Verlag, Tokyo.

- Noe, R., de Waal, F.B., Van Hooff, J., 1980. Types of dominance in a chimpanzee colony. Folia Primatol. (Basel) 34 (1–2), 90–110.

- Ogura, T., 2013. A digital app for recording enrichment data. Shape Enrich. 22, 3.

- Palagi, E., Paoli, T., 2007. Play in adult bonobos (Pan paniscus): modality and potential meaning. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 134 (2), 219–225. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ajpa. 20657.

- Palagi, E., Cordoni, G., Borgognini Tarli, S.M., 2004. Immediate and delayed benefits of play behaviour: new evidence from chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Ethology 110 (12), 949–962. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0310.2004.01035.x.

- Palagi, E., Paoli, T., Tarli, S.B., 2006. Short-term benefits of play behavior and conflict prevention in Pan paniscus. Int. J. Primatol. 27 (5), 1257–1270. http://dx.doi.org/10. 1007/s10764-006-9071-y.

- Palagi, E., 2006. Social play in bonobos (Pan paniscus) and chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes): Implicationsfor natural social systems and interindividual relationships. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 129 (3), 418–426. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.20289.

- Pellis, S.M., Iwaniuk, A.N., 2000. Adult-adult play in primates: comparative analyses of its origin, distribution and evolution. Ethology 106 (12), 1083–1104. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1046/j.1439-0310.2000.00627.x.

- Pellis, S.M., 2002. Sex differences in play fighting revisited: traditional and nontraditional mechanisms of sexual differentiation in rats. Arch. Sex. Behav. 31 (1), 17–26. http:// dx.doi.org/10.1023/a:1014070916047.

- R Development Core Team, 2011. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. (3-900051-07-0). http://www.R-project.org/.

- Ross, S.R., Wagner, K.E., Schapiro, S.J., Hau, J., 2010. Ape behavior in two alternating environments: comparing exhibit and short-term holding areas. Am. J. Primatol. 72 (11), 951–959.

- Sharpe, L.L., Cherry, M.I., 2003. Social play does not reduce aggression in wild meerkats. Anim. Behav. 66 (5), 989–997. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/anbe.2003.2275.

- Sharpe, L.L., 2005. Play does not enhance social cohesion in a cooperative mammal. Anim. Behav. 70 (3), 551–558. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2004.08.025.

- Shimada, M., Sueur, C., 2014. The importance of social play network for infant or juvenile wild chimpanzees at Mahale Mountains National Park, Tanzania. Am. J. Primatol. 76 (11), 1025–1036. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ajp.22289.

- Silk, J.B., Alberts, S.C., Altmann, J., 2003. Social bonds of female baboons enhance infant survival. Science 302 (5648), 1231–1234. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science. 1088580.

- Silk, J.B., Alberts, S.C., Altmann, J., 2006. Social relationships among adult female baboons (Papio cynocephalus) II. Variation in the quality and stability of social bonds. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 61 (2), 197–204. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00265-006- 0250-9.

- Silk, J.B., Beehner, J.C., Bergman, T.J., Crockford, C., Engh, A.L., Moscovice, L.R., Cheney, D.L., et al., 2010. Strong and consistent social bonds enhance the longevity of female baboons. Curr. Biol. 20 (15), 1359–1361. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cub. 2010.05.067.

- Ventura, R., Majolo, B., Koyama, N.F., Hardie, S., Schino, G., 2006. Reciprocation and interchange in wild Japanese macaques: grooming, cofeeding, and agonistic support. Am. J. Primatol. 68 (12), 1138–1149. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ajp.20314.

- Videan, E.N., Fritz, J., 2007. Effects of short- and long-term changes in spatial density on the social behavior of captive chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 102 (1–2), 95–105. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2006.03.011.

- Walsh, S., Bramblett, C.A., Alford, P.L., 1982. A vocabulary of abnormal behaviors in restrictively reared chimpanzees. Am. J. Primatol. 3 (1–4), 315–319. http://dx.doi. org/10.1002/ajp.1350030131.

- Wittig, R.M., Crockford, C., Weltring, A., Deschner, T., Zuberbühler, K., 2015. Single aggressive interactions increase urinary glucocorticoid levels in wild male chimpanzees. PLoS One 10 (2), e0118695. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0118695.

- Wittig, R.M., Crockford, C., Weltring, A., Langergraber, K.E., Deschner, T., Zuberbühler, K., 2016. Social support reduces stress hormone levels in wild chimpanzees across stressful events and everyday affiliations. Nat. Commun. 7, 13361. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncomms13361. http://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms13361# supplementary-information.

- Yamanashi, Y., Morimura, N., Mori, Y., Hayashi, M., Suzuki, J., 2013. Cortisol analysis of hair of captive chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 194 (0), 55–63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ygcen.2013.08.013.

- Yamanashi, Y., Teramoto, M., Morimura, N., Hirata, S., Inoue-Murayama, M., Idani, G., 2016a. Effects of relocation and individual and environmental factors on the longterm stress levels in captive chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes): monitoring hair cortisol and behaviors. PLoS One 11 (7), e0160029. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0160029.

- Yamanashi, Y., Teramoto, M., Morimura, N., Hirata, S., Suzuki, J., Hayashi, M., Idani, G., et al., 2016b. Analysis of hair cortisol levels in captive chimpanzees: effect of various methods on cortisol stability and variability. Methods X 3, 110–117. http://dx.doi. org/10.1016/j.mex.2016.01.004.

Table 1. Information of observed social groups.

| Group type | Number of groups | Number of males | Number of females | Age range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-male group | 2 | 11 | 0 | 15–40 |

| Mixed-sex group | 5 | 6 | 20 | 9–43 |

Table 2. Ethogram of social behaviours.

| Behaviours | Definitions |

|---|---|

| Social Behaviours | |

| Aggressive interactions | Behaviours that included chasing, hitting, biting, kicking, and charging displays directed toward group members; individuals who were targets of such behaviour showed screaming, escaping, or counterattacking behaviours. |

| Social play | Playing with conspecifics. The behaviours included play push, play bite, play slap, tickle, play run, grab hands or legs repeatedly and rhythmically, social object play, rough and tumble and play stamping. These behaviours sometimes appeared sequentially. Social play is distinguishable from other social behaviours since all the social play sessions in this study included play face or play pants. |

| Social grooming | Groom another with hands or mouth. Mutual grooming included the grooming which two chimpanzees groom each other simultaneously. Groom unilateraly included the grooming another without reciprocation. |

| Self-directed Behaviours | |

| Self-grooming | Pick through and/or slow brushing aside of one's own hair or skin with the mouth and/or one or two hands. |

| Self-scratch | Rake one's own hair or skin with fingernails. |

| Abnormal Behaviours | |

| Coprophagy | Ingestion of feces. |

| Feces Smearing | Spreading of feces on a surface with the hands and/or mouth. Frequently accompanied by coprophagy. |

| Hair pluck | Pulling out of own or another animal’s hair. |

| Pacing | Locomote, usually quadrupedally, on substrate, covering and then re-covering route in stylized fashion, with no clear objective. |

| Regurgitation and reingestion | Deliberate, repetitive regurgitation typically accomplished by lowering the head to the ground. The vomitus is retained within the mouth and reingested. |

| Rocking | Repetitive seated, bipedal, or quadrupedal rocking. |

| Suck hair | Sucking hair of own body. |

Table 3. Sex composition of social play bouts.

| Sex combination | Observed | Expected |

|---|---|---|

| Male – Male | 1 | 0.74 |

| Male – Female | 22 | 11.5 |

| Female – Female | 6 | 16.7 |

Table 4. Results of statistical testing of timing of social play and social grooming.

| Time | Rate of behaviours (Mean ± SE) | Estimate | SE | T | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unilateral social grooming | |||||

| 11:00 | 0.0189 ± 0.0116 | ||||

| 11:30 | 0.0607 ± 0.0162 | −33.8 | 16.2 | −2.09 | 0.0404* |

| 12:00 | 0.0857 ± 0.0297 | −37.8 | 15.9 | −2.39 | 0.0198* |

| 12:30 | 0.107 ± 0.0440 | −39.7 | 15.7 | −2.52 | 0.0141* |

| 13:00 | 0.0837 ± 0.0289 | −37.6 | 15.9 | −2.37 | 0.0206* |

| 13:30 | 0.0755 ± 0.0262 | −36.6 | 16.0 | −2.29 | 0.0250* |

| 14:00 | 0.109 ± 0.0273 | −39.8 | 15.7 | −2.53 | 0.0137* |

| 14:30 | 0.116 ± 0.0260 | −40.2 | 15.7 | −2.56 | 0.0127* |

| Mutual social grooming | |||||

| 11:00 | 0.0184 ± 0.00860 | ||||

| 11:30 | 0.0233 ± 0.0106 | −4.00 | 27.6 | −0.145 | 0.885 |

| 12:00 | 0.0985 ± 0.0276 | −28.6 | 20.9 | −1.36 | 0.177 |

| 12:30 | 0.130 ± 0.0322 | −29.8 | 20.8 | −1.43 | 0.157 |

| 13:00 | 0.0598 ± 0.0210 | −25.1 | 21.4 | −1.17 | 0.246 |

| 13:30 | 0.0903 ± 0.0274 | −27.8 | 21.0 | −1.32 | 0.190 |

| 14:00 | 0.113 ± 0.0273 | −29.0 | 20.9 | −1.39 | 0.170 |

| 14:30 | 0.104 ± 0.0286 | −28.6 | 20.9 | −1.37 | 0.177 |

| Social play | |||||

| 11:00 | 0.00117 ± 0.00117 | ||||

| 11:30 | 0.0106 ± 0.00597 | −783 | 484 | −1.62 | 0.110 |

| 12:00 | 0.0132 ± 0.00559 | 789 | 484 | −1.63 | 0.108 |

| 12:30 | 0.0337 ± 0.0123 | −812 | 483 | −1.68 | 0.0973+ |

| 13:00 | 0.0182 ± 0.00767 | −801 | 484 | −1.66 | 0.102 |

| 13:30 | 0.00727 ± 0.00329 | −749 | 486 | −1.54 | 0.128 |

| 14:00 | 0.00982 ± 0.00377 | −778 | 485 | −1.65 | 0.113 |

| 14:30 | 0.0309 ± 0.00872 | −813 | 483 | −1.68 | 0.0969+ |

* p < 0.05, + 0.05 < p < 0.10.

Fig. 1. Age and social play. Blue filled circles represent data of males from all-male

groups and blue outlined circles represent those from mixed-sex groups. Red circles represent

data of females.

Fig. 1. Age and social play. Blue filled circles represent data of males from all-male

groups and blue outlined circles represent those from mixed-sex groups. Red circles represent

data of females.

Fig. 2. Differences of the rate of social play (2-a), social grooming (2-b) and aggressive interactions (2-c) between different social groups.

Fig. 2. Differences of the rate of social play (2-a), social grooming (2-b) and aggressive interactions (2-c) between different social groups.

** p < 0.01.

Fig. 3. Distribution of aggressive interactions across the day.

Fig. 3. Distribution of aggressive interactions across the day.

Fig. 4. Relationship between social play, social grooming and aggressive interactions in all-male group chimpanzees. Fig. 4-a showed the relationship between mutual social grooming and aggressive interactions. Fig. 4-b showed the relationship between grooming equality index and aggressive interactions. Fig. 4-c showed the relationship between social play and aggressive interactions. Fig. 4-d showed the relationship between social play and grooming equality index. Fig. 4-e showed the relationship between social play and mutual social grooming. A photo of social play (Fig. 4-f).

Fig. 4. Relationship between social play, social grooming and aggressive interactions in all-male group chimpanzees. Fig. 4-a showed the relationship between mutual social grooming and aggressive interactions. Fig. 4-b showed the relationship between grooming equality index and aggressive interactions. Fig. 4-c showed the relationship between social play and aggressive interactions. Fig. 4-d showed the relationship between social play and grooming equality index. Fig. 4-e showed the relationship between social play and mutual social grooming. A photo of social play (Fig. 4-f).

Article Information

Yamanashi, Y., Nogami, E., Teramoto, M., Morimura, N., & Hirata, S.(2017)Adult-adult social play in captive chimpanzees: is it indicative of positive animal welfare? Applied Animal Behaviour Science

, 199: 75-83

10.1016/j.applanim.2017.10.006