Role of mothers in the acquisition of tool-use behaviours by captive infant chimpanzees.

Satoshi Hirata, Maura L. Celli

DOI: 10.1007/s10071-003-0187-6Abstract

This article explores the maternal role in the acquisition of tool-use behaviours by infant chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). A honey-fishing task, simulating ant/termite fishing found in the wild, was introduced to three dyads of experienced mother and naïve infant chimpanzees. Four fishing sites and eight sets of 20 objects to be used as tools, not all appropriate, were available. Two of the mothers constantly performed the task, using primarily two kinds of tools; the three infants observed them. The infants, regardless of the amount of time spent observing, successfully performed the task around the age of 20–22 months, which is earlier than has been recorded in the wild. Two of the infants used the same types of tools that the adults predominantly used, suggesting that tool selectivity is transmitted. The results also show that adults are tolerant of infants, even if unrelated; infants were sometimes permitted to lick the tools, or were given the tools, usually without honey, as well as permitted to observe the adult performances closely.

Keywords

Acquisition, Chimpanzees, Mother-infant, Tool use, Transmission

Introduction

Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) have an immense behavioural/feeding species repertoire, as well as an already well-documented set of cultural traditions among different communities (McGrew 1992; Whiten et al. 1999). Much of this knowledge depends on postnatal learning processes (Biro et al. 2003).

Within a period of around 5 years, chimpanzee infants develop and use their mothers as models for observation and imitation. Using the example of nut cracking, a form of tool use observed among wild chimpanzees in parts of West Africa, Matsuzawa and colleagues applied the term "master-apprenticeship" to characterise the relational basis of infants' education (Matsuzawa et al. 2001). Their comments can be summarised as follows: The so-called master-apprenticeship relationship is common in many traditional human societies, where knowledge and skills can be transmitted from one person to another without verbal explanation, molding, or written instructions; the master does not provide any form of active teaching, but the apprentice is expected to possess a strong motivation to imitate.

From Matsuzawa et al.'s (2001) study of nut-cracking behaviours at Bossou, Guinea, the following picture emerged. A chimpanzee master does not actively teach the chimpanzee apprentice, but the apprentice acquires a skill through long-term repetitive observation of the master, supported by high levels of tolerance on the master's part, such as allowing access to nuts, tools, and cracked-open kernels. In contrast, Boesch (1991) described a kind of demonstration teaching among Taï chimpanzee mothers, who would go through nut-cracking motions more slowly when the offspring was watching, or correct the positioning of a nut on the anvil for the infant. However, only two episodes of active teaching were recorded over decades of observation.

An important question to consider is the degree to which infants spontaneously observe their masters. That is, how often does an infant observe his/her mother before mastering a skill? And to what extent does the mother tolerate infant observation? What kinds of interaction occur between a mother and infant during the infant's acquisition of tool use? The extent of the maternal role in the learning process of chimpanzee infants is still unexplored. Therefore, our aim in this study was to examine the chimpanzee master-apprenticeship system by presenting longitudinal, quantitative data on the behaviour of mother–infant pairs and the choice of tools during tool-use learning.

Methods

Subjects and housing conditions

The subjects were three adult female chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) and their respective offspring, cared for at the Primate Research Institute of Kyoto University. The names of the mothers and their ages at the onset of the study were Ai (24 years), Chloe (19 years), and Pan (16 years). Ai gave birth to a male, AYUMU, on 24 April 2000; Chloe gave birth to a female, CLEO, on 19 June 2000; and Pan gave birth to a female, PAL, on 9 August 2000. Note that the names of the mothers and their offspring each start with the same letter, and the names of the infants will appear in uppercase throughout this article to distinguish mothers from infants.

All three infants were cared for by their mothers. All adult subjects served in several experiments on perception and cognitive capacities, before and after giving birth to their infants (Biro and Matsuzawa 1999; Fujita and Matsuzawa 1990; Kawai and Matsuzawa 2000; Kojima 1990; Myowa-Yamakoshi and Matsuzawa 1999; Sousa and Matsuzawa 2001; Tanaka 1995; Tomonaga 1998). Furthermore, before they became pregnant, the adults had also participated in tool-use experiments, using artificial materials or leaves to drink juice (M.L. Celli, unpublished data; Tonooka et al. 1997) or to fish for honey (M.L. Celli and S. Hirata, unpublished data; Hirata and Morimura 2000). The subjects lived in a community, together with eight other chimpanzees, in a facility consisting of a large outdoor compound of approximately 700 m2, and two smaller compounds with wire mesh roofs, all enriched with streams, plants, and climbing structures (Ochiai and Matsuzawa 1997). The chimpanzees were fed three times a day with fruits, vegetables, and chow; they were never deprived of food while experiments were conducted. Water was available ad libitum.

Materials and task

The task presented was a simulation of ant- or termite-fishing behaviour observed among wild chimpanzees across Africa, in which honey was used as a reward. Forty grams of honey was poured into transparent polyethylene bottles (4.0×2.5×6.0 cm) that were attached to polycarbonate panels from the outside, beyond the chimpanzees' reach. Each panel had a 5-mm-diameter hole in its centre, providing access to an opening in the bottle. Two identical sites, with two panels each (total of four panels with hole and bottle attached), 1.9 m apart, were prepared for honey fishing. The panels in each site were positioned at two different heights: for the upper panels the hole was 87 cm from the floor, and for the lower panels the hole was 43 cm from the floor.

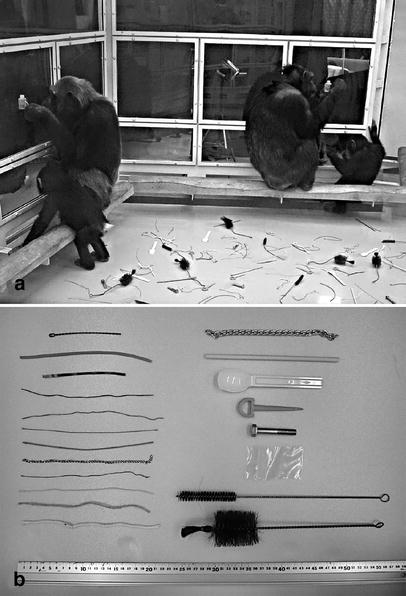

Eight sets of 20 artificial materials to be used as tools (total of 160 objects) of various shapes and sizes, ranging from 6.5 to 32.0 cm in length and 1–50 mm in width, were scattered randomly in the experimental room within 2 m2 of the sites (Fig. 1a, b). Not all of the materials were appropriate for the task. From each set, 12 materials were considered task appropriate (namely, knobbly plastic string, rubber tube, vinyl string, silver wire, green wire, thin metal rope, thick metal rope, thin chain, nylon string, cotton string, hemp string, and vinal string), as they could be inserted into the hole. Eight materials were considered inappropriate (namely, thick chain, chopstick, spoon, plastic pin, metal bolt, plastic pouch, thin brush, and thick brush), as they could not be inserted into the hole because of their size. All three adult subjects had prior experience with these materials and this setting as part of a series of previous experiments (M.L. Celli et al., unpublished data; Hirata and Morimura 2000). Of the 20 kinds of materials, all three mothers showed a preference for certain types of material for use in honey fishing; this preference was based on their previous experiences with a number of these materials. In the majority of cases, Ai used the knobbly plastic string, and Chloe and Pan used the rubber tube (M.L. Celli et al., unpublished data; Hirata and Morimura 2000). The infants had never seen or manipulated these materials before.

Fig. 1. a Lateral view of the experimental room with all four panels for honey fishing, tools scattered on the floor and mother–infant dyads. b Twenty kinds of materials provided as tools. Left, top to bottom: knobby plastic string, rubber tube, vinyl string, silver wire, green wire, thin metal rope, thick metal rope, thin chain, nylon string, cotton string, hemp string, and vinal string. Right, top to bottom: thick chain, chopstick, spoon, plastic pin, metal bolt, plastic pouch, thin brush, and thick brush

Procedure

Two mother–infant pairs were tested together in an experimental room (approximately 30 m2) with the bottles attached to each of the four panels and the eight sets of materials scattered on the floor. All possible combinations of the two mother–infant pairs were tested; these tests usually took place twice a month from November 2000 until August 2002, except when tests were cancelled because of illness or other events. In the initial sessions, conducted during the first 3 months, the dyad of mother–infant Pan and PAL was not included. Thus, the experiment started when the three infants were 5–7 months old. A single session lasted for 40 min. All sessions were recorded by five video cameras. Two cameras were fixed in front of the panel at each honey-fishing site, two cameras recorded the chimpanzees' behaviours during the sessions, and one camera recorded the experimental room from above.

Data analysis

Video tapes were analysed to examine the behaviour of both infants and mothers during the honey-fishing experiments. The behaviours were classified into several categories, as defined in Table 1. Infants' observations of other individuals fishing for honey were coded only when they were within arm's reach, as an individual performing honey fishing faced a panel within a distance of approximately 20 cm, and an infant had to move close to it to view clearly the use of a tool and the honey bottle. Although the possibility exists that an infant could observe tool-use behaviour from a distance, such cases were ambiguous in terms of an infant's observation of others' tool-using activity, and hence such cases were not counted.

|

Category |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Observe |

Observing another individual's honey-fishing activity within arm's reach for more than 1 s (shorter glances were omitted). Bouts started when an infant turned its gaze on another individual with a tool and ended when the infant went outside arm's reach, or when the infant stopped watching for more than 3 s though staying within arm's reach, or when the individual stopped using the tool. If the infant turned its gaze on an unrelated target (i.e., a target that was neither a tool, nor an individual using the tool, nor a honey bottle) and returned its gaze to the honey-fishing activity within 3 s, it was included in the observation bout |

|

Reach |

Approaching with hand or mouth to within 3 cm of a tool being used by another individual. Includes cases in which the infant actually made contact with the tool |

|

Touch |

Contact using hand, lip, or tongue with a tool being used by another individual |

|

Lick |

Holding in the mouth a tool being used by another individual |

|

Remove |

Taking away a tool being used by another individual |

|

Attempt |

Sequence of behaviours that began when an infant oriented a part of a tool to the hole and the tool touched within 5 cm of the hole. The attempt ended when the infant detached the tool from the panel and when that detached state continued for more than 1 s. If the tool detached from the panel and touched the panel again within 1 s, this sequence was considered as one attempt |

|

Rejecta |

Holding a hand, mouth, face, or head and pushing it away from the tool, or moving the tool in the opposite direction to the infant's reaching |

|

Allowa |

Stopping a movement to insert or retrieve a tool, thus allowing an infant to touch/lick the tool, or releasing the tool, thus allowing an infant to take it |

|

Give |

Holding out the tip of a tool that is in use by the individual to an infant's mouth, face, or hand |

aReaction to an infant's reaching (on the part of mothers, unrelated adult females, or another infant)

When an infant reached for a tool being used by another individual, and the individual reacted, two tool states were distinguished: (1) "tool with honey" was defined as an infant reaching for the tool after the other individual had inserted it into the honey, but before that individual had licked it; (2) "tool without honey" meant that an infant reached for the tool after the other individual had licked honey from the tool, but before the next insertion into the honey.

The total duration in seconds for each behavioural category was calculated and represented in percentage values. Frequency was indicated when appropriate. Fisher's exact tests were applied for the comparison of proportions throughout the article, because the expected values were less than 5 in some data sets. Chi-square tests were also applied whenever possible, but because their results were practically identical to those of Fisher's exact test on the same data sets and did not alter the level of significance, only the results of the Fisher's exact tests will be presented. In addition, when sets of proportional data involving multiple factors were compared, proportional data were transformed using an arcsine transformation method and analysed against the chi-square distribution, to examine the effect of one of the factors on differences in the proportions (Mori and Yoshida 1990).

Comparison with the performance of adults

The infants' selection of tools before their first success was compared with the tool selections made by adults when Hirata and Morimura (2000) tested them as naïve subjects in their study. The materials used were identical. There were two conditions in the study by Hirata and Morimura (2000): a single-subject condition, and a pair condition in which naïve chimpanzees were tested with experienced partners. However, the results of the analysis of behaviours during the acquisition process did not differ statistically between these two conditions (Hirata and Morimura 2000); therefore, we pooled the data from these two conditions and compared the results for all nine naïve adults' attempts before their first success with those of the infants in this study.

Results

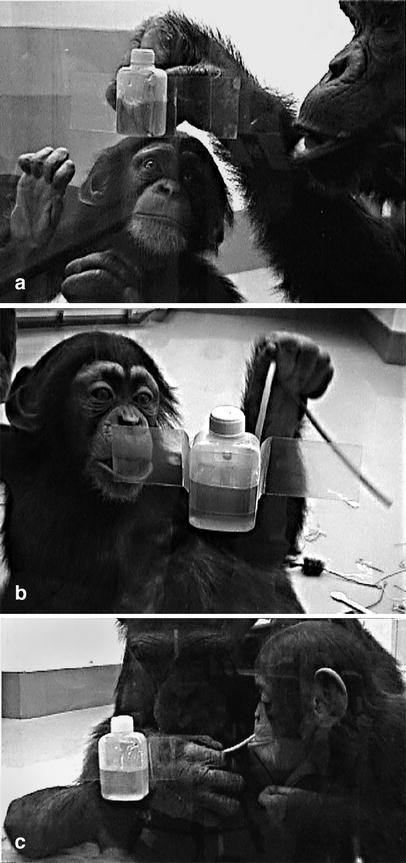

Two of the three mothers, Ai and Chloe, continued to fish successfully for honey throughout the sessions. Each offspring observed, from a close distance, his/her mother, as well as an unrelated adult, fishing for honey (Fig. 2a, see also video clip S1 in the electronic supplementary material). The other mother, Pan, successfully fished for honey in two sessions at the beginning but soon stopped doing so and did not resume afterwards. She stayed in another smaller room connected to the experimental area, about 5 m away from the honey-fishing site, during almost all sessions. This limited her offspring's opportunity to observe other individuals' honey-fishing activity, as the infant, PAL, tended to stay near her mother.

Fig. 2. a An infant (AYUMU) observing his mother's (Ai) activity of honey fishing. b An infant (AYUMU) attempting to insert a tool (rubber tube) into the honey hole when he was 1 year and 8 months old. c A mother (Ai) giving the tip of a tool to her infant (AYUMU)

Observation of others

Tables 2, 3, and 4 show the data for infants' observation of others engaging in honey fishing, from their first session until their first successful attempts at fishing for honey. For AYUMU (Table 2), the number of bouts of observation of his mother, and the duration of these observations, fluctuated across months. When the study began, AYUMU, then 7 months old, did not observe another unrelated adult, Chloe. Starting at 8 months of age, the number of bouts of observation of unrelated adult and their duration per session constantly increased for AYUMU, up to 11 months of age, and then fluctuated across the months. For CLEO (Table 3), observations of maternal behaviour increased when she reached 10–11 months of age. Initially, CLEO stayed near her mother and did not observe another unrelated adult, Ai. Gradually, she began to move further from her mother, and she observed an unrelated adult when she was 14, 15, and 16 months old. As for PAL (Table 4), her mother successfully fished honey in two sessions at the beginning of the study, when PAL was 5 months old; PAL observed her mother fishing for honey in these sessions. PAL also observed another unrelated adult, Chloe, twice during these sessions. However, PAL's mother did not perform honey fishing after PAL was 6 months old, as described above. As PAL developed and became more independent, she gradually began to wander away from her mother, Pan; PAL observed other individuals' performances closely after she was 15 months old.

|

Target |

Age (months) |

Total |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

20 |

21 |

||

|

Ai |

||||||||||||||||

|

Number of sessions conducted |

4 |

1 |

4 |

2 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

54 |

|

Total number of bouts |

42 |

6 |

33 |

7 |

28 |

32 |

31 |

33 |

19 |

53 |

35 |

54 |

14 |

70 |

27 |

484 |

|

Total duration (s) |

837 |

43 |

427 |

203 |

515 |

924 |

627 |

641 |

241 |

1,028 |

555 |

866 |

181 |

728 |

429 |

8,245 |

|

Chloe |

||||||||||||||||

|

Number of sessions conducted |

4 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

30 |

|

Total number of bouts |

0 |

3 |

13 |

8 |

22 |

15 |

13 |

12 |

6 |

5 |

13 |

10 |

6 |

8 |

12 |

146 |

|

Total duration (s) |

0 |

60 |

276 |

171 |

485 |

361 |

285 |

188 |

192 |

102 |

250 |

384 |

103 |

102 |

184 |

3,143 |

|

Target |

Age (months) |

Total |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

20 |

||

|

Chloe |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Number of sessions conducted |

4 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

1 |

57 |

|

Total number of bouts |

27 |

2 |

4 |

14 |

5 |

9 |

16 |

23 |

26 |

33 |

38 |

33 |

39 |

37 |

45 |

2 |

353 |

|

Total duration (s) |

409 |

51 |

56 |

136 |

47 |

91 |

403 |

570 |

467 |

688 |

664 |

393 |

600 |

479 |

517 |

48 |

5,619 |

|

Ai |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Number of sessions conducted |

4 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

27 |

|

Total number of bouts |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

10 |

4 |

|

|

|

|

16 |

|

Total duration (s) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

15 |

275 |

201 |

|

|

|

|

491 |

|

Target |

Age (months) |

Total |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

5 |

15 |

16 |

21 |

||

|

Pan |

|||||

|

Number of sessions conducted |

2 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

65 |

|

Total number of bouts |

5 |

|

|

|

5 |

|

Total duration (s) |

110 |

|

|

|

110 |

|

Chloe |

|||||

|

Number of sessions conducted |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

34 |

|

Total number of bouts |

2 |

12 |

11 |

5 |

30 |

|

Total duration (s) |

31 |

259 |

181 |

45 |

516 |

|

Ai |

|||||

|

Number of sessions conducted |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

34 |

|

Total number of bouts |

|

|

3 |

4 |

7 |

|

Total duration (s) |

|

|

25 |

40 |

65 |

|

CLEO |

|||||

|

Number of sessions conducted |

|

|

|

2 |

34 |

|

Total number of bouts |

|

|

|

1 |

1 |

|

Total duration (s) |

|

|

|

27 |

27 |

|

AYUMU |

|||||

|

Number of sessions conducted |

|

|

|

2 |

34 |

|

Total number of bouts |

|

|

|

7 |

7 |

|

Total duration (s) |

|

|

|

64 |

64 |

PAL was not recorded as observing others when she was 6–14, 17–20, and 22 months old, before her first success.

The main targets of observations by the three infants were the two proficient mothers, Ai and Chloe. Both adults selectively used 2 types of tools from among the 20 kinds available: the knobbly plastic string and the rubber tube. When being observed by infants, Ai used the knobbly plastic string 87% of the time, the rubber tube 7% of the time, and other materials 6% of the time. Chloe used the knobbly plastic string 24% of the time, the rubber tube 70% of the time, and other materials 6% of the time. In addition to these two individuals, Pan, AYUMU, and CLEO were observed by the last infant, PAL, for shorter periods of time. When observed by PAL, Pan used the knobbly plastic string 45% of the time and the rubber tube 55% of the time; AYUMU used the knobbly plastic string 64% of the time, the rubber tube 0% of the time, and other materials 36% of the time; CLEO used the rubber tube 100% of the time.

The three infants observed two types of tool use almost exclusively. AYUMU spent 7,724 s (68%) observing the use of the knobbly plastic string, 2,982 s (26%) observing the use of the rubber tube, and 682 s (6%) observing the use of other tools. CLEO spent 1.906 s (31%) observing the use of the knobbly plastic string, 3,988 s (65%) observing the use of the rubber tube, and 216 s (4%) observing the use of other tools. PAL spent 513 s (66%) observing the use of the knobbly plastic string, 246 s (31%) observing the use of the rubber tube, and 23 s (3%) observing the use of other tools.

Infants' first success and selection of tools for attempts

AYUMU first succeeded in fishing for honey by himself using a knobbly plastic string when he was 21 months old. CLEO first succeeded when she was 20 months old; she also used the knobbly plastic string. PAL succeeded by using a rubber tube when she was 22 months old (see video clip S5 in the electronic supplementary material). Table 5 shows the number of honey-fishing attempts by the infants before their first success, as a function of age. All infants' first attempts occurred several months before their first success, and the number of attempts greatly increased a month prior to their first success (Fig. 2b).

|

|

Age in months |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

20 |

21 |

22 |

|

|

AYUMU |

4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 |

73 |

|

|

CLEO |

|

|

|

|

|

8 |

1 |

11 |

8 |

|

|

|

PAL |

|

|

|

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

84 |

3 |

Table 6 shows the infants' selection of tools for their attempts before their first success. Two of the three infants, AYUMU and PAL, attempted to fish honey using, predominantly, either the knobbly plastic string or the rubber tube, which had been used by other individuals most frequently. They chose these two tools for their attempts considerably more often than would have been the case if they had chosen randomly from the 20 kinds of tools (binomial test, P<0.001). The third infant, CLEO, attempted to fish honey using a wider range of tools, although she also selected either the knobbly plastic string or the rubber tube more often than would have occurred by chance (binomial test, P=0.0033).

|

|

AYUMU |

CLEO |

PAL |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Number of attempts |

84 |

28 |

89 |

|

With knobbly plastic string |

25 |

9 |

12 |

|

With rubber tube |

59 |

4 |

67 |

|

With other tools |

0 |

15 |

10 |

|

Number of tools used |

20 |

21 |

38 |

|

Knobbly plastic string |

7 |

4 |

7 |

|

Rubber tube |

13 |

3 |

25 |

|

Others |

0 |

14 |

6 |

|

Number of tool types used |

2 |

8 |

8 |

Comparison with adults

When we look at the performance of naïve adults in this situation, as reported in Hirata and Morimura (2000), the proportion of attempts with rubber tubes or knobbly plastic string by the nine adults before their first successes, along with the number of tool types used, were as follows: 0/4 (three types), 0/4 (three types), 0/20 (six types), 0/12 (three types), 0/14 (four types), 15/40 (eight types), 0/3 (one type), 0/1 (one type), 0/0 (the last individual first succeeded at the first attempt with a rubber tube). Two of the nine first succeeded using the rubber tube, and no individual first succeeded using the knobbly plastic string. The remaining seven individuals first succeeded when using tools other than the knobbly plastic string or rubber tube. Six of the nine individuals gradually began to select the rubber tube or the knobbly plastic string more frequently in the later stages. The remaining three failed to use the tools skillfully to fish for honey and stopped attempting to do so in the later stages of the study.

A comparison between the data for adults and the data for infants showed that the infants selected rubber tubes or knobbly plastic string more frequently in their attempts before their first success than did adults (Mann–Whitney U test, U(3, 9)=2.5, P=0.023).

Mother–infant interactions

Two of the infants consistently reached for the tools that the adults were using (Tables 7, 8). AYUMU reached for the tools his mother was using 295 times, and for Chloe's tool (an unrelated adult female) 46 times. CLEO reached for her mother's tools 503 times, and for Ai's tools 70 times. The other infant, PAL, showed reaching behaviour just once, toward Chloe's tools. The infants sometimes succeeded in touching, licking, or stealing the tools. For AYUMU, reaching behaviour appeared at an earlier period and peaked at about 1 year. After the peak, the frequency of reaching behaviours decreased and, after 17 months, AYUMU seldom reached for another individual's tools. For CLEO, the frequency of reaching behaviours towards her mother's tools was initially low; it increased when she was about 1 year old and remained high throughout the rest of the study.

|

|

Age in months |

Total |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

20 |

21 |

||

|

Reaching for Ai's tools with honey |

15 |

|

14 |

6 |

21 |

28 |

16 |

10 |

|

18 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

131 |

|

Ai: Allowed to lick |

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

Ai: Rejected |

2 |

|

|

2 |

5 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

|

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

16 |

|

Reaching for Ai's tools without honey |

2 |

|

17 |

8 |

24 |

62 |

16 |

14 |

2 |

12 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

|

2 |

164 |

|

Ai: Allowed to lick |

|

|

3 |

3 |

4 |

16 |

3 |

2 |

|

3 |

|

1 |

1 |

|

1 |

37 |

|

Ai: Rejected |

|

|

3 |

|

1 |

14 |

7 |

2 |

|

1 |

1 |

|

1 |

|

|

30 |

|

Reaching for Chloe's tools with honey |

|

|

5 |

3 |

19 |

5 |

|

3 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

40 |

|

Chloe: Allowed to lick |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

Chloe: Rejected |

|

|

4 |

1 |

5 |

3 |

|

2 |

|

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

17 |

|

Reaching for Chloe's tools without honey |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

|

Chloe: Allowed to lick |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

Chloe: Rejected |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

Age in months |

Total |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

20 |

||

|

Reaching for Chloe's tools with honey |

9 |

6 |

11 |

8 |

6 |

5 |

19 |

24 |

26 |

33 |

31 |

33 |

26 |

36 |

16 |

|

289 |

|

Chloe: Allowed to lick |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

2 |

1 |

5 |

3 |

4 |

2 |

1 |

|

|

19 |

|

Chloe: Rejected |

6 |

4 |

3 |

8 |

4 |

4 |

11 |

10 |

22 |

15 |

12 |

22 |

14 |

23 |

6 |

|

164 |

|

Reaching for Chloe's tools without honey |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

2 |

20 |

19 |

6 |

40 |

37 |

40 |

19 |

14 |

13 |

|

214 |

|

Chloe: Allowed to lick |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

8 |

3 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

|

18 |

|

Chloe: Rejected |

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

11 |

8 |

3 |

19 |

18 |

27 |

12 |

11 |

6 |

|

117 |

|

Reaching for Ai's tools with honey |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

14 |

6 |

|

|

|

|

20 |

|

Ai: Allowed to lick |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

Ai: Rejected |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

Reaching for Ai's tools without honey |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

11 |

10 |

|

|

|

|

23 |

|

Ai: Allowed to lick |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

2 |

6 |

|

|

|

|

10 |

|

Ai: Rejected |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

We also examined the two adults' reactions to the two infants' reaching behaviours (PAL was excluded because of the small sample size). Both adults allowed the infants to lick their tools when they had no honey smeared on them (i.e., after they themselves had licked the honey or before inserting the tool into the honey bottle) more frequently than they did when the tools were covered with honey, except for the Chloe–CLEO pair (Fisher's exact test, Ai–AYUMU pair, P<0.001; Ai–CLEO pair, P=0.0050; Chloe–CLEO pair P=0.49; Chloe–AYUMU pair P=0.014).

Based on the data as shown in Tables 7 and 8, comparisons of the rates of allowing or rejecting the infant to lick the tool were made between mother–offspring and mother–unrelated pairs (see video clips S2 and S3 in the electronic supplementary material). For the adult Ai, the proportion of times her offspring was allowed to lick a tool was lower than that for unrelated infants for tools with honey, 2% for her offspring versus 5% for the unrelated infants; for tools without honey, the proportion was 23% for her offspring compared to 43% for unrelated infants. For Chloe, her offspring was allowed to lick a tool with honey 7% of the time, whereas the unrelated infant was not allowed (0%). For tools without honey, Chloe's offspring was allowed to lick 8% of the time, compared to 33% for the unrelated infant. Analysis of the rejection of the infants' reaching behaviours showed that for Ai, rejection rates were higher for her offspring (12%) than for the unrelated infant (5%) for tools with honey, as well as for tools without honey: 18% for her offspring, compared to 9% for the unrelated infant. For Chloe, rejection rates were higher for her offspring (57%) than for the unrelated infant (43%) for tools with honey, and for tools without honey 52% for her offspring, compared to 17% for the unrelated infant. Overall, mothers were not more tolerant of their own infants than they were of unrelated infants. A statistical analysis of the proportions, treating the type of mother–infant pairs (mother–offspring or mother–unrelated infant) and tool states (tools with or without honey) as different factors showed that the rates of allowing infants to lick the tools were not significantly different for their own offspring compared to unrelated infants (χ2=2.38, df=1, P=0.12). On the other hand, the rejection rate was higher for their own offspring than for unrelated infants (χ2=10.17, df=1, P=0.0014).

To assess changes in the adults' reactions as the infants developed, the study period was divided into the first and second half (AYUMU, 7–14 and 15–21 months old; CLEO, 5–12 and 13–20 months old). The proportions with respect to allowing or rejecting infant tool licking on the part of adults for the first half were compared to those for the second half, with study period (first or second half), mother–infant pairs, and tool states (tools with or without honey) as different factors. The rate to allow did not differ statistically for the two time periods (χ2=0.60, df=1, P=0.44). The rate of rejection also did not differ statistically between the first and second halves of the study period (χ2=0.17, df=1, P=0.68). To consider the possible changes in adults' reactions further, we examined the rates before and after the infants began continued attempts to use the tools themselves (AYUMU, 7–19 and 20–21 months old; CLEO, 5–16 and 17–20 months old). AYUMU showed reaching behaviour only twice after 20 months, which was when he started frequently to attempt fishing by himself; thus, for AYUMU, statistical comparison was not possible. For CLEO, her mother's rate of allowing licking did not differ before and after she began to make attempts by herself at 17 months of age (Fisher's exact test, tools with honey, P=0.42; tools without honey, P=0.54). Furthermore, her mother's rejection rate for licking did not differ before and after CLEO was 17 months old (Fisher's exact test, tools with honey, P=0.79; tools without honey, P=0.24). CLEO did not exhibit reaching behaviour to Ai after she began to make her own attempts.

Both adult mothers were observed to give the tip of the tool they were using, or the entire tool, to the infants (Fig. 2c, see also video clip S4 in the electronic supplementary material). All but one of the cases involved tools without honey. Ai gave her offspring AYUMU a tool smeared with honey once, when the infant was 12 months old, and 15 times without honey; this giving behaviour occurred sporadically throughout the study period, and less than 3 times per session. Ai never gave CLEO, an unrelated infant, tools with honey but was observed 7 times to give her tools without honey when the infant was 15 and 16 months old. Chloe gave AYUMU (unrelated infant) tools without honey 3 times, when the infant was 11, 12, and 15 months old. She was not observed to give tools with honey to her offspring CLEO, but she did give CLEO tools without honey 10 times sporadically throughout the study period, and less than 3 times a session. Most of the giving behaviour occurred in reaction to infants' reaching, touching, or licking the adults' tools. There were six other cases. Three cases occurred without any preceding, explicit action from infants. In these cases, an infant approached an adult, began quietly observing, and then the adult held out a part of a tool to the infant. Two other cases occurred when infants blocked the hole in front of an adult. An infant moved in front of an adult and started to lick the empty hole where the adult had tried to insert her tool; in this instance the adult held out a part of a tool to the infant's mouth. One final case occurred when Chloe left a tool inserted in the hole and AYUMU reached for the tool. In this case, Chloe had another tool in her hand, and gave this tool to AYUMU. There were no cases in which the infants used tools given by adults to make their own attempts. No other behaviours were observed that could be regarded as teaching, such as slowly showing a model, assisting an infant's attempt, or vocal or behavioural encouragement of an infant's attempt.

Discussion

We observed the sequence of the process of learning tool use by infant chimpanzees to evaluate the master-apprenticeship of chimpanzee education.

At least two of the infants spent a considerable amount of time in the experiment observing their mothers perform honey fishing. The mother–infant bond is intense, and proximity is such that it leads to the infant's repeated observation of, and sometimes participation in, the mother's activities. Such situations result in frequent opportunities for stimulus enhancement, social facilitation, true imitation, and the like (Galef 1988). In our study, however, the infants observed not only their respective mother's performances, but also other adult's. This finding is consistent with the results of observations in the wild by Inoue-Nakamura and Matsuzawa (1997), who found that as infants developed, they spent more time observing chimpanzees other than their own mothers. The implication is that mothers are an important resource, but not the only resource, for models of tool use in the social community of chimpanzees. Infants other than their own offspring are allowed to approach mothers for close observation, an experience cited as a form of education in wild chimpanzees (Matsuzawa et al. 2001).

PAL, who had less exposure to maternal honey-fishing behaviour because of her mother's lack of interest, succeeded at 1 year and 10 months, around the same age as the other infants. AYUMU first succeeded at the age of 1 year and 9 months and CLEO at 1 year and 8 months. In another study of object manipulation by the same three infants (Hayashi and Matsuzawa 2003), the frequency of combinatory manipulation (i.e., orienting an object to another object) dramatically increased at around 1.5 years old, just before the infants' first successful tool use in the present study. As the three ages are similar, we suggest that, in part, successful tool use reflects the cognitive-motor development of the infants.

The acquisition of honey-fishing skills by the captive chimpanzees observed here occurred earlier than the acquisition of ant-fishing skills in the wild, where the earliest age reported is 2 years and 8 months (Nishida and Hiraiwa 1982). Proficiency at ant fishing in the wild was shown to require 6–7 years of experience (McGrew 1977), whereas termite-fishing required only 4–5 years (Teleki 1974). According to Chevalier-Skolnikoff (1983), captive orangutans could perform a honey-fishing task at around 3–4 years of age. The only study of acquisition by young chimpanzees in captivity, also for honey fishing, tested four subjects between the age of 7 and 8 (Paquette 1992). There are several possible reasons for the notable difference in ages between our study and others. Our task may have been easier, as ants in the wild sting and must be avoided by various complicated methods, whereas honey is immobile and harmless. Another possibility is that the prolonged exposure to skilled individuals in our study might have had a facilitating effect, though direct comparison and discussion of this point is not possible because there are no data available on the frequency of tool-use observation in the wild. It is possible that the captive environment, which provides many more opportunities to manipulate a variety of objects, might have accelerated the development of manipulation. Detailed observations of the development of tool use in the wild are necessary to evaluate these possibilities. Putting these issues aside, our study clearly showed that chimpanzee infants developed tool-using skills, which entailed inserting an object into a hole to obtain an otherwise inaccessible food item, just before they reached 2 years of age.

The infants selectively used 2 items from among 20 different objects as tools for their attempts. Their mothers predominantly used these two tools and the infants frequently observed them being used. The infant chimpanzees in this study were seen to observe the entire trajectory of the use of the honey-fishing tool, and we suggest that the observation of the means and not just the end might have drawn them to their particular tool selections. However, the proportion of time that the infants' observed these two tools being used did not match the proportion of time that they spent on their own attempts with each of these two tools. Thus, the infants' attempts were not a complete reflection of their observations. Other factors such as differences in the size, hardness, and flexibility of the tools might have influenced their preferences for handling certain types of tools.

However, we would like to point out that the present article reports on the infants' attempts before their first successes, that is, a situation in which none of the infants' manipulatory behaviour of tools was rewarded or reinforced. Still, two infants continued overwhelmingly to select the same two tools. These two tools are known to be the most efficient for fishing honey (M.L. Celli, unpublished data); therefore, the adults had learned to select these two kinds of materials through their own trial-and-error experiences with a variety of materials (Hirata and Morimura 2000). On the one hand, the number of naïve adults' attempts before their first success was smaller than that of infants, indicating that the adults could solve the problems that the task posed relatively easily. On the other hand, even the adults did not initially realize which tools were the most efficient before their first successes. The results for the infants in the present study support the view that, at least in part, they acquired tool selectivity by observing adults; this finding demonstrates the importance of mothers or other skilled individuals in infant acquisition of tool use. Tonooka (2001) showed that both adult and infant wild chimpanzees at Bossou, Guinea, selected a particular kind of leaf to use for drinking water. An initial bias for the particular material may be acquired by infants' longitudinal observation of adults, which leads, in turn, to the formation of a local tradition in the selection of tool materials (McGrew 1992; Sugiyama 1993).

The adults sometimes rejected the infants' involvement in their tool-use activities, and at other times allowed infants to touch, lick, or take their tools. Our results show that infants were allowed to lick a tool more often when the tool was not smeared with honey. These findings indicate that the adults did not directly bring the benefit to the infants (i.e., give them honey), and hence the behaviour of the adults is not strong evidence for active teaching (Caro and Hauser 1992). Behaviours such as slowly showing a model, as described by Boesch (1991), assisting an infant's attempt, and vocal or behavioural encouragement of an infant's attempt were never observed. Human mothers in the same situation would probably give a child a tool coated in honey, hold a tool and a child's hand, and assist in the insertion of the tool, with verbal or behavioural encouragement (Bard and Vauclair 1984).

Boesch and Boesch-Achermann (2000) presented an analysis of maternal aid in wild chimpanzees during nut cracking; assistance such as leaving the hammer behind on the anvil for the infant or providing the infant with a better hammer or intact nuts was observed. Their results show that mothers provided aid to infants only when the infants could benefit, and not when the infant was either incapable of solving the task or could solve the task independently. To probe whether the mothers in the present study changed their behaviour towards the infants as they developed, we looked at the proportions of allowing and rejecting with respect to tool licking, especially before and after the infants began to attempt the task for themselves. The results show that the maternal attitude towards the infants appeared to be fairly constant, with the proviso that only one of the three infants was a suitable subject for this analysis.

Taken together, our observations of chimpanzees are consistent with previous findings that chimpanzees generally do not teach others (Matsuzawa et al. 2001). In contrast to the results for Taï chimpanzees (Boesch 1991), no other field studies have provided observations of individuals using special techniques to help learners achieve mastery of tool use. Instead, younger chimpanzees have the opportunity to observe older ones performing the tasks. According to King (1994), infants demonstrate the capacity for behaving interactively with adults (i.e., observing and reaching for their tools) to increase their chances of obtaining information from more experienced individuals, who rarely offer information to them.

In addition to the absence of clear examples of active teaching by mothers in this study, however, the adult females sometimes ceased their behaviour when approached by infants (in the case of both their offspring and the unrelated infants); they did allow the infants, at times, to lick the tool (especially when it was not covered with honey). In other cases, the adults gave a tool without honey to an infant (both to their own offspring and to an unrelated infant). Even if the patterns of allowing or giving that were observed in the present study do not completely fit within the constraints of active teaching, the maternal experience of giving the tools, or allowing an infant to access the tools, might indicate an evolutionary foundation for human teaching. As Boesch and Boesch-Achermann (2000) suggested, the mothers' generosity may provide the infants with an incentive to attempt to acquire the skill without giving up partway. Whether such tolerant behaviours are specific to adult–infant relationships or change when both adults and infants are skilled at a technique is a question that needs further investigation before we can clarify evolutionary changes in styles of socially mediated learning processes.

While describing human cultural changes, Greenfield et al. (2000) defined apprenticeship processes as an important key to behavioural ontogeny in a species that must, in the course of a lifetime, acquire knowledge and transmit it. From the behaviours that we observed in the present study, we can draw similarities to human systems for the transmission of knowledge (Greenfield et al. 2000). These similarities are possibly a common evolutionary foundation for teaching and learning processes in both humans and chimpanzees and may constitute one of the important steps in the establishment of culture in humans.

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture, Japan (Grants 07102010, 12002009, 10CE2005, and JSPS-2926). We would like to thank N. Bacon, C. Douke, M. Hayashi, T. Imura, Y. Mizuno, N. Nakashima, G. Ohashi, C. Sousa, A. Ueno, and M. Uozumi for their assistance in data collection, and T. Matsuzawa, M. Tomonaga, and M. Tanaka for their support and suggestions. Thanks are also due to K. Kumazaki, N. Maeda, and other staff at the Primate Research Institute of Kyoto University for their support in conducting the experiment and for taking care of the chimpanzees. The experiment reported here adhered to the 1986 version of the "Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Primates" of the Primate Research Institute of Kyoto University. The experiments described complied with the current laws of Japan.

References

- Bard KA, Vauclair J (1984) The communicative context of object manipulation in ape and human adult-infant pairs. J Hum Evol 13:181–190

-

Biro D, Matsuzawa T (1999) Numerical ordering in a chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes): planning, executing, and monitoring. J Comp Psychol 113:178–185

- Biro D, Inoue-Nakamura N, Tonooka R, Yamakoshi G, Sousa C, Matsuzawa T (2003) Cultural innovation and transmission of tool use in wild chimpanzees: evidence from field experiments. Anim Cogn DOI 10.1007/s10071-003-0183-x

- Boesch C (1991) Teaching among wild chimpanzees. Anim Behav 41:530–532

- Boesch C, Boesch-Achermann H (2000) The chimpanzees of the Taï forest: behavioural ecology and evolution. Oxford University Press, New York

-

Caro TM, Hauser MD (1992) Is there teaching in nonhuman animals? Q Rev Biol 67:151–174

- Chevalier-Skolnikoff S (1983) Sensorimotor development in orang-utans and other primates. J Hum Evol 12:545–561

-

Fujita K, Matsuzawa T (1990) Delayed figure reconstruction by a chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) and humans (Homo sapiens). J Comp Psychol 104:345–351

- Galef BG (1988) Imitation in animals: history, definition and interpretation of data from the psychological laboratory. In: Zentall T, Galef BG (eds) Social learning: psychological and biological perspectives. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, N.J., pp 3–28

- Greenfield PM, Maynard AE, Boehm C, Schmidtling EY (2000) Cultural apprenticeship and cultural change: tool learning and imitation in chimpanzees and humans. In: Parker ST, Langer J, McKinney ML (eds) Biology, brains and behavior—the evolution of human development. School of American Research Press, Santa Fe, N.M., pp 237–277

- Hayashi M, Matsuzawa T (2003) Cognitive development in object manipulation by infant chimpanzees. Anim Cogn DOI 10.1007/s10071-003-0185-8

-

Hirata S, Morimura N (2000) Naïve chimpanzees' (Pan troglodytes) observation of experienced conspecifics in a tool-using task. J Comp Psychol 114:291–296

-

Inoue-Nakamura N, Matsuzawa T (1997) Development of stone tool use by wild chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). J Comp Psychol 111:159–173

-

Kawai N, Matsuzawa T (2000) Numerical memory span in a chimpanzee. Nature 403:39–40

- King BJ (1994) Primate infants as skilled information gatherers. Pre Perinat Psychol J 8:287–307

-

Kojima S (1990) Comparison of auditory functions in the chimpanzee and human. Folia Primatol 55:62–72

- Matsuzawa T, Biro D, Humle T, Inoue-Nakamura N, Tonooka R, Yamakoshi G (2001) Emergence of culture in wild chimpanzees: education by master-apprenticeship. In: Matsuzawa T (ed) Primate origins of human cognition and behavior. Springer, Tokyo Berlin Heidelberg, pp 557–574

- McGrew WC (1977) Socialization and object manipulation of wild chimpanzees. In: Chevalier-Skolnikoff S, Poirier F (eds) Primate biosocial development: biological, social and ecological determinants. Garland STPM Press, New York, pp 261–288

- McGrew WC (1992) Chimpanzee material culture. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

- Mori T, Yoshida T (1990) Technical book of data analysis for psychology (in Japanese). Kitaoji, Kyoto

-

Myowa-Yamakoshi M, Matsuzawa T (1999) Factors influencing imitation of manipulatory actions in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). J Comp Psychol 113:128–136

- Nishida T, Hiraiwa M (1982) Natural history of a tool-using behavior by wild chimpanzees in feeding upon wood-boring ants. J Hum Evol 11:73–99

- Ochiai T, Matsuzawa T (1997) Planting trees in an outdoor compound of chimpanzees for an enriched environment. In: Hare V (ed) Proceedings of the third international conference on environmental enrichment congress. The Shape of Enrichment, San Diego, Calif., pp 355–364

- Paquette D (1992) Discovering and learning tool-use for fishing honey by captive chimpanzees. Hum Evol 7:17–30

-

Sousa C, Matsuzawa T (2001) The use of tokens as rewards and tools by chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Anim Cogn 4:213–221

- Sugiyama Y (1993) Local variation of tools and tool use among wild chimpanzee populations. In: Berthelet A, Chavaillon J (eds) The use of tools by humans and nonhuman primates. Clarendon Press, Oxford, pp 175–187

-

Tanaka M (1995) Object sorting in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes): classification based on physical identity, complementarity, and familiarity. J Comp Psychol 109:151–161

- Teleki G (1974) Chimpanzee subsistence technology: materials and skills. J Hum Evol 3:575–594

-

Tomonaga M (1998) Perception of shape from shading in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) and humans (Homo sapiens). Anim Cogn 1:25–35

-

Tonooka R (2001) Leaf-folding behavior for drinking water by wild chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus) at Bossou, Guinea. Anim Cogn 4:325–334

-

Tonooka R, Tomonaga M, Matsuzawa T (1997) Acquisition and transmission of tool making and use for drinking juice in a group of captive chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Jpn Psychol Res 39:253–265

-

Whiten A, Goodall J, McGrew W, Nishida T, Reynolds V, Sugiayama Y, Tutin C, Wrangham R, Boesch C (1999) Culture in chimpanzees. Nature 399:682–685