A note on the responses of chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) to live self-images on television monitors.

Satoshi Hirata

DOI: 10.1016/j.beproc.2007.01.005Abstract

The majority of studies on self-recognition in animals have been conducted using a mirror as the test device; little is known, however, about the responses of non-human primates toward their own images in media other than mirrors. This study provides preliminary data on the reactions of 10 chimpanzees to live self-images projected on two television monitors, each connected to a different video camera. Chimpanzees could see live images of their own faces, which were approximately life-sized, on one monitor. On the other monitor, they could see live images of their whole body, which were approximately one-fifth life-size, viewed diagonally from behind. In addition, several objects were introduced into the test situation. Out of 10 chimpanzees tested, 2 individuals performed self-exploratory behaviors while watching their own images on the monitors. One of these two chimpanzees successively picked up two of the provided objects in front of a monitor, and watched the images of these objects on the monitor. The results indicate that these chimpanzees were able to immediately recognize live images of themselves or objects on the monitors, even though several features of these images differed from those of their previous experience with mirrors.

1. Introduction

Great apes can use a mirror to inspect areas of their body not visible without the aid of the mirror, suggesting that they have the capacity for self-recognition, although evidence is limited in gorillas (Inoue-Nakamura, 1997). Since the pioneering work by Gallup (1970), many studies have examined mirror behavior in many species of primates and other animals, including elephants and dolphins ( [Itakura, 1987], [Povinelli, 1989] and [Marino et al., 1994]).

The majority of the studies of self-recognition in animals have been conducted using a mirror as the test device (Anderson, 1984). Little is known about non-human primates’ responses toward their own image in media other than a mirror (see Anderson, 1999 for a review). Law and Lock (1994) reported that gorillas respond differently to live-videotapes of self versus delayed videotapes of self and others. Savage-Rumbaugh (1984) provided a descriptive report of two chimpanzees, who had had much experience in watching TV programs and live events happening elsewhere in their facility on TV monitors, beginning to show signs of self-recognition on a monitor. The two chimpanzees investigated the image on the monitor by making unusual facial gestures, moving their tongues, lips, hands, and feet, and holding various body postures. One of the two chimpanzees investigated the inside of its throat by opening its mouth in front of the camera, and the other chimpanzee painted its face with red pigment while watching the monitor. These descriptions clearly indicate that the chimpanzees are able to recognize images on a monitor recorded with a live-video camera; however, quantitative data, including the duration of live-video exposure and latency to their first self-exploratory behaviors, are not presented in this report.

Another study showed that chimpanzees can use the live image on a video monitor to locate an otherwise hidden object (Menzel et al., 1985). Poss and Rochat (2003) also showed, in a slightly different experiment, that chimpanzees and one orangutan were successful in finding a reward hidden in one of two areas when they were able to view the hiding event on a video monitor. Eddy et al. (1996) described that chimpanzees responded differently to a self-image in a mirror versus a videotaped image of other chimpanzees.

A live image on a monitor has several features that are different from a reflection in a mirror (Savage-Rumbaugh, 1984). First, the left–right orientation in a video image is the opposite of that in the reflection in a mirror. Second, by placing the video camera at various angles, live images of the body from angles other than the front can be shown easily on a monitor. Third, the sizes of the images on a monitor can be magnified or reduced more easily, and to a greater extent, than can those of mirror images.

In this study, the reactions of chimpanzees to live self-images on television, with the above-mentioned features, were investigated; this was part of a pilot study to examine the possibility of using video media to investigate self-recognition in chimpanzees. Two television monitors were set up; each connected to a different video camera. One monitor showed a live image of the scene in front of the monitor, particularly the face or head of the chimpanzee facing the monitor. The left–right orientation in this monitor was the reverse of the reflection in a mirror. The other monitor was connected to another video camera, filming a wide view from the opposite side of the room. When a chimpanzee sat in front of the monitor, its whole body, as viewed diagonally from behind, appeared on the monitor. In addition, several objects were introduced to assess recognition of the relationship between the real objects and those appearing on the second monitor.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Subjects and housing conditions

The subjects were 10 adult chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) at the Primate Research Institute of Kyoto University, Inuyama, Aichi, Japan. There were three males (Gon, 32 years; Akira, 22 years; Reo, 16 years) and seven females (Puchi, 32 years; Ai, 22 years; Mari, 22 years; Pendesa, 21 years; Chloe, 18 years; Popo, 16 years; Pan, 15 years). Before this experiment, some of the chimpanzees had taken part in various experiments on perception and cognitive capacities (see Matuzawa, 2003 for a review). All of the chimpanzees live together in an outdoor compound containing a semi-natural enriched environment, with a rich social life that included interactions with conspecifics and humans. The chimpanzees were fed various fruits and vegetables three times a day. Water was freely available, and the chimpanzees were never food deprived.

2.2. Mirror experiences of the subjects

Detailed quantitative data for the subjects on the frequency and duration of past experiences with mirrors were unavailable owing to a lack of written records; however, the following offers a brief outline of past mirror experiences (Matsuzawa et al., pers. commun.). Popo, Reo, and Pan were exposed to mirrors about once per month for tests of cognitive development from shortly after birth until 1 year of age. After that, they had been shown mirrors a few times a year during daily contact with human caretakers and researchers. Ai, Akira, Mari, Pendesa, and Chloe had been shown mirrors a few times a year during daily contact with human caretakers and researchers since their arrival at the Primate Research Institute (Ai, 1 year; Akira, 1.5 years; Mari, 1.5 years; Pendesa, 2 years; Chloe, 4 years). Gon and Puchi were kept as pets by private individuals until they were 10 years old, and there was no information whether they had seen mirrors during this period. These two chimpanzees received no mirror exposure after their arrival at the Primate Research Institute, but like the other chimpanzees they could see reflective surfaces such as stainless steel walls of their housing facility in their daily lives. The sizes of mirrors shown to the chimpanzees varied, but a portable mirror about 30 cm × 40 cm was used in many of the cases. Evidence of mirror self recognition is available only for Ai and Chloe (Matsuzawa, 1991). They were seen to investigate teeth or eyelids while watching mirrors, and they passed a mark test similar to that of Lin et al.'s (1992) procedure. There was no record of self-recognition behaviors, i.e., self-directed or self-exploratory behaviors, during mirror exposure, for the remaining individuals (Popo, Reo, Pan, Akira, Mari, Pendesa, Gon, and Puchi), but the author had occasionally seen Puchi rubbing her head while watching the reflective surfaces of an outdoor experimental room in the chimpanzees’ enclosure.

2.3. Apparatus and materials

A 20 m2 polygonal playroom was used for the test. The room had transparent walls made of polycarbonate panels. Two 14 in. (35 cm) color monitors (monitors A and B) were placed side by side outside the playroom, facing a transparent wall panel. The height of the monitors was adjusted using pedestals to the eye level of the chimpanzee sitting in front of the monitor. Video camera A was fixed on top of monitor A and the picture-output was connected to monitor A. Video camera B was fixed in front of another transparent panel, approximately 3 m away from monitor B at an angle of 135°, and connected to monitor B. When a chimpanzee sat in front of the monitors, camera A filmed its face or head, and the live picture appeared on monitor A; camera B filmed its whole body diagonally from behind and this image was shown on monitor B. The size of the face or head appearing on monitor A was roughly life-size; that of the body on monitor B was approximately one-fifth life-size. The reason for the arrangement of these sizes is that the camera filming the back was adjusted so that the whole body, from the bottom to the top, would appear on the monitor to make the form of the body image well recognizable from the back, which resulted in approximately one-fifth life-size. The other camera filming the face or head was zoomed out at maximum, yielding an image of the face or head approximately life-size on the monitor when the chimpanzees sat in front of the camera. A 30 cm × 45 cm mirror was used to test for mirror self-recognition. The mirror was placed in approximately the same position as the two monitors used for the above-mentioned test. Seven objects were introduced to the testing situation to encourage manipulation in front of the monitors and the mirror. These objects were: a 10 cm high plastic cup, a 25 cm long plastic rake, a 30 cm long plastic scoop, a plastic plate 15 cm in diameter, a plastic pin 10 cm long, a pigtail brush 30 cm long, and a 10 cm × 17 cm piece of cloth.

2.4. Procedure

Each subject participated in three sessions of live-video exposure and one session of mirror exposure. Each chimpanzee was individually exposed to live self-images on the monitors, for 30 min in Session 1 and for 10 min in Session 2. For Session 3 the 10 chimpanzees were assigned to 5 pairs (Pan & Popo, Chloe & Mari, Gon & Reo, Pendesa & Puchi, and Ai & Akira) and each pair was exposed to the live image on the monitors for 20 min. Session 4 was mirror exposure, in which each chimpanzee was individually exposed to the mirror for 20 min. The background for the differing length of these sessions was as follows. During the first session in which each individual was brought to the testing room for 30 min, some of the chimpanzees showed signs of being agitated; therefore, the length of the next session was shortened. Because some of the chimpanzees still appeared agitated during the second session, the two chimpanzees that had an affinitive relationship were brought together in the third session, which incorporated a longer duration than the second session by taking into consideration the time the two chimpanzees spent interacting with each other. The duration of the mirror exposure was the average of the three sessions of the video exposure. All of the chimpanzees were tested in the above order. Each session was separated by at least 5 days, and the time of a session varied across sessions. A chimpanzee or pair of chimpanzees was brought into the playroom and allowed to behave freely for approximately 10 min before the start of a session. A session started when the experimenter switched on the monitors or placed the mirror in position. The two monitor screens were switched off before the start of a video session. To start the session, the experimenter approached the monitors and switched them on in rapid succession; thus the scenes from the video cameras connected to each of the monitors were shown. The sound of the monitors was muted. For the mirror session, the experimenter brought the mirror to a predetermined position and placed it. Although no particular attempts were made to make sure that the chimpanzees noticed the switching on the monitors or placement of the mirror, they always paid attention to the experimenter approaching the monitors or positioning the mirror. After the start of a session, subjects were left to behave freely in the playroom. A session ended when the experimenter switched off the monitors or removed the mirror. The chimpanzees’ behaviors during the test sessions were video-recorded by the two video cameras (cameras A and B) used to show the live image of the chimpanzees, and by another video camera handled by the experimenter.

2.5. Data analysis

The following behaviors were coded from the videotapes: social behavior, contingent movement, self-exploratory behavior, and object-related behavior. Every instance of each behavior was written down on a checksheet. These behavioral categories were adapted from Lin et al. (1992) and Povinelli et al. (1993). Social behavior refers to a chimpanzee directing social behaviors (e.g., head bobbing, swaggering, charging with hair erect) at the monitor or the mirror. Contingent movement consists of repetitive movement of the head or body, or unusual facial contortions, while visually following the movement on the monitor or the mirror (e.g., moving the arm up and down rapidly). Self-exploratory behavior was defined as manipulating parts of one's own body, not otherwise visible, with the hands or fingers (e.g., turning over the lip while looking at one's own face or rubbing the back of the head while looking at the image of the back of one's own body). Object-related behavior was defined as exploring the correspondence between the objects that appeared on the monitor or in the mirror and their real world counterpart. This consisted of manipulating an object while watching it on the monitor or in the mirror. In addition, the time spent looking at each monitor or the mirror was scored. The author first analyzed all of the videotapes. A second, independent, coder analyzed the data from one randomly chosen session for each individual. The occurrence of each reaction scored by the first coder corresponded completely to the score recorded by the second coder. In the categorization of these reactions, agreement between the first and second coder was also high (91% agreement, Cohen's κ = 0.87). The agreement for the measurement of the time spent looking at each monitor was calculated from a second-by-second scoring of the occurrence of subjects looking at the monitors. The observed agreement was 95.5% (Cohen's κ = 0.84).

3. Results

Two chimpanzees, Chloe and Puchi, showed self-exploratory behaviors in all of the test sessions. The other individuals did not show self-exploratory behaviors in any sessions, except one individual who showed self-exploratory behavior only in the mirror session (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Table 2 shows the time each individual spent viewing the live self-images on each monitor. There was no significant difference in the time spent looking at the two monitors, one of which showed a self-image of the face and the other that of the back (sign test, n = 10 for each session, Session 1, p = 0.34; Session 2, p = 1.00; Session 3, p = 1.00). Similarly, the two individuals who showed self-exploratory behaviors did not look differentially at the two monitors although the sample size was too small to conduct a statistical test. The frequency of contingent movements and self-exploratory behaviors in these two individuals in each self-image in each session is shown in Fig. 2. Both chimpanzees showed self-exploratory behaviors towards the face or head and towards the back using the live self-images. No significant bias in the number of self-exploratory behaviors towards the face/head or the back was found (binomial test, p = 0.42 for Chloe and p = 0.09 for Puchi).

| Chloe | Puchi | Gon | Ai | Akira | Mari | Pendesa | Reo | Popo | Pan | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Live video | ||||||||||

| Social behavior | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| Contingent movement | 7 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Self-exploratory behavior | 14 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mirror | ||||||||||

| Social behavior | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Contingent movement | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Self-exploratory behavior | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

Fig. 1. A female chimpanzee investigating the reverse side of her lower lip while looking at her own face on the monitor showing exactly the same view as this picture.

| Individual | V1 | V2 | V3 | Mirror | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Front | Back | Front | Back | Front | Back | ||

| Chloe | 33 | 66 | 61 | 37 | 11 | 50 | 55 |

| Puchi | 14 | 165 | 49 | 4 | 39 | 15 | 261 |

| Gon | 94 | 56 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 4 | 0 |

| Ai | 4 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 46 |

| Akira | 37 | 14 | 5 | 10 | 4 | 4 | 51 |

| Mari | 56 | 24 | 5 | 28 | 1 | 32 | 513 |

| Pendesa | 4 | 13 | 5 | 1 | 32 | 0 | 89 |

| Reo | 104 | 46 | 13 | 32 | 0 | 7 | 299 |

| Popo | 38 | 12 | 1 | 18 | 6 | 8 | 40 |

| Pan | 57 | 32 | 36 | 45 | 9 | 6 | 71 |

| Mean | 44 | 43 | 18 | 18 | 12 | 13 | 143 |

Notes: V1, V2, and V3 are video sessions 1, 2, and 3, respectively, in which chimpanzees were exposed to live self-images taken through video cameras. Front: the monitor showing the front of the face or head of the chimpanzees; back: the monitor showing the back of the chimpanzees diagonally.

Fig. 2. Number of times each behavioral response was shown by two chimpanzees, Chloe and Puchi, in each session of the exposure to live self-images on the two monitors. These individuals engaged in self-exploratory behaviors while watching the monitor or the mirror showing the front of the face or head (SE-front) and the monitor showing the back of the body diagonally (SE-back), and contingent movements while watching the monitor or the mirror showing the front of the face or head (CM-front) and the monitor showing the back of the body diagonally (CM-back). V1, V2, and V3: Sessions 1, 2, and 3 of live-video exposure, respectively; M: mirror exposure.

Chloe's first reaction was self-exploration of her head, then inside her ear, 8 min and 32 s from the start of the first session after having looked at herself on the monitors for a total of 51 s. Puchi's first reaction was self-exploration of the back of her head, 19 min and 39 s from the start of the first session after having looked at herself on the monitors for a total of 62 s. These self-exploratory behaviors were targeted only to the body part visible on the monitor. Among all self-exploratory behaviors observed, those involving body parts that could be viewed on the monitor showing a close-up view of the face or head (but not on the monitor showing the back) included stroking the front of the head, inserting a finger into the ear, touching a nostril, turning over and manipulating the lips, and touching the tongue and teeth; these behaviors were observed while the chimpanzees were looking at the monitor showing a close-up view of the face or head but did not occur while they were looking at the other monitor. Self-exploratory behaviors involving body parts that could be viewed on the monitor showing the back of the body (but not on the monitor showing a close-up view of the face) included stroking and manipulating the back of the head and investigating the genital and rump areas; these behaviors were observed while the chimpanzees were looking at the monitor showing the back of the body but did not occur while they were looking at the other monitor.

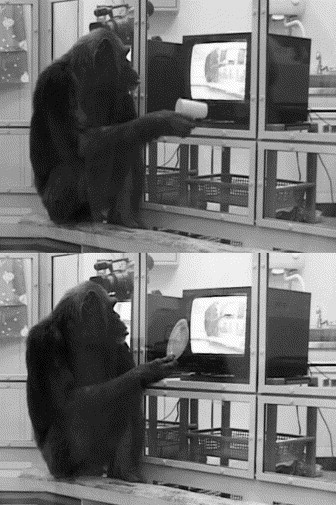

Object-related behavior was seen only once in one of these two chimpanzees (Fig. 3). In her first session, Chloe picked up a plastic cup and watched it on the monitor, not looking at the real object. After 11 s, she placed the cup on the floor and picked up a plastic plate which she watched on the monitor for 7 s. Then she put the plate underneath a bench attached to the wall while looking at the monitor, and then put the plate on the floor. After placing the plate on the floor, she moved away from the monitor.

Fig. 3. A female chimpanzee picked up a plastic cup (top) and a plastic plate (bottom) in succession, and watched the images on the monitor, not the real objects in her hand.

4. Discussion

This experiment showed that two chimpanzees with experience of mirrors used live-video images to investigate their own body. They inspected parts of their face not otherwise visible, although the orientation of left and right was the reverse of that of their previous experience with a mirror. They also explored the back of their body while looking at the monitor; the absolute size of the image was much reduced from life-size. In addition, the object-directed behavior shown by one individual indicates that this chimpanzee not only recognized self, but also environmental objects. These reactions can be considered in relation to chimpanzees’ recognition of the relationship between maps, scale models, or photographs and the corresponding real-world objects ( [Menzel et al., 1978], [Menzel et al., 1985], [Kuhlmeier et al., 1999], [Kuhlmeier and Boysen, 2001] and [Kuhlmeier and Boysen, 2002]). As suggested by Anderson (2001), the capacity for visual perspective taking may play an important role in the understanding of images in a mirror or on a television monitor. In a study by Poss and Rochat (2003), chimpanzees were able to use video to guide their search for a hidden object. The authors suggested that these chimpanzees had the ability to acquire relevant information about where the objects were hidden and then to transpose and map video information onto real space. The result of the current study is consistent with their discussion. Whether it is an object in the environment or the animal's own body, at least some chimpanzees were able to transpose and map video information onto correspondent targets in the real world; this ability could be observed, without a delay, even when the perceptual characteristics of video information were somehow new and different from those in a mirror. However, the data from this study are limited, and further investigations, with more intensive data collection and detailed analyses, are warranted.

The level of responsiveness to the self-image was lower in 8 out of 10 chimpanzees, as has been observed in studies of mirror self-recognition ( [Swartz and Evans, 1991] and [Povinelli et al., 1993]). However, one of these chimpanzees, Ai, did show evidence of mirror self-recognition in a previous study (Matsuzawa, 1991). When she was 8 years old she investigated her teeth while watching a mirror, and removed small stickers surreptitiously placed on her left ear and above her eyelid. Self-exploratory behaviors while mirror-watching were observed occasionally in Ai after this study, during daily contacts with experimenters. She did not pay much attention to her live-video or mirror images during the present study, conducted when she was 22 years old. In a cross-sectional study involving 92 chimpanzees, Povinelli et al. (1993) reported that only 26% of the older adults (16–32 years) exhibited self-exploratory behaviors during mirror exposure, compared to 75% of the subjects aged 8–15 years. Furthermore, a follow up study with the same subjects found that some of the adolescent individuals who had shown mirror self-recognition did not provide compelling evidence 8 years later (de Veer et al., 2003). Although the present study is on a much smaller scale, the results are in accordance with those of Povinelli et al. (1993) and de Veer et al. (2003). Further research is needed to clarify causes of individual variation and possible decline as a function of age in the expression of self-exploratory behaviors while watching self-images.

Although the mark test, a robust experimental procedure developed by Gallup (1970) to confirm self-recognition was not applied in this study, the self-exploratory behaviors shown by the two individuals can be considered as positive evidence (Povinelli et al., 1993). In these two chimpanzees, the latency from the start of exposure to live self-images until the first appearance of self-exploratory behavior was short. This study showed that their capacity for self-recognition is not specific to a mirror image, but can be generalized to a different medium without difficulty. Gallup (1994) stated, “To became a bona fide scientific fact, an observation must be replicated by different observers, in different settings, on different subjects”. Boysen et al. (1994) showed that chimpanzees can also recognize their own shadows. In their study, a spotlight behind the chimpanzee was used to cast shadows against a wall faced by the chimpanzee, and an experimenter raised a hat behind the chimpanzee so that its shadow appeared to be wearing a hat. One of the tested chimpanzees reacted to this by reaching up and behind to touch the hat and by shifting downward and disengaging from the shadow of the hat. This example provides evidence of shadow self-recognition. Taken together, the phenomenon of self-recognition in chimpanzees is clearly a scientific fact.

In contrast to a reflection in a mirror, images on a television screen can be manipulated in many ways. In addition to showing live self-images as in the present study, it is possible to show delayed or transformed self-images, or images of other individuals on a television monitor. Researchers have utilized such features to examine the nature of self-recognition in human infants (e.g., Miyazaki and Hiraki, 2006). Video self-recognition opens a window for further evaluation of the nature of chimpanzee self-recognition than has been possible with mirrors.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks T. Matsuzawa for his generous guidance throughout the project. Thanks are also due to K. Kumazaki, N. Maeda, and other staff at the Primate Research Institute of Kyoto University for support in conducting the experiment and for taking care of the chimpanzees, and M. Uchikoshi for assistance in data analysis. This research was financed by Research Fellowship 9773 from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science for Young Scientists, JSPS-HOPE, and Grant 12002009 and 1870266 from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan. The experiment reported here adhered to the 1986 version of the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Primates” of the Primate Research Institute of Kyoto University.

References

- J.R. Anderson Monkeys with mirrors: some questions for animal psychology Int. J. Primatol., 5 (1984), pp. 81–97

- J.R. Anderson Primates and representations of self Curr. Psychol. Cogn., 18 (1999), pp. 1005–1029

- J.R. Anderson Self and others in nonhuman primates: a question of perspective Psychologia, 44 (2001), pp. 3–16

- S.T. Boysen, K.M. Bryan, T.A. Shreyer Shadows and mirrors: alternative avenues to the development of self-recognition in chimpanzees S.T. Parker, R.W. Mitchell, M.L. Boccia (Eds.), Self-awareness in Animals and Humans: Developmental Perspectives, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1994), pp. 227–240

- M.W. de Veer, G.G. Gallup, L.A. Theall, R. van den Bos, D.J. Povinelli An 8-year longitudinal study of mirror self-recognition in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) Neuropsychologia, 41 (2003), pp. 229–234

- T.J. Eddy, G.G. Gallup, D.J. Povinelli Age difference in the ability of chimpanzees to distinguish mirror-images of self from video images of others J. Comp. Psychol., 110 (1996), pp. 38–44

- G.G. Gallup Chimpanzees: self-recognition Science, 167 (1970), pp. 86–87

- G.G. Gallup Self-recognition: research strategies and experimental design S.T. Parker, R.W. Mitchell, M.L. Boccia (Eds.), Self-awareness in Animals and Humans: Developmental Perspectives, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1994), pp. 35–50

- N. Inoue-Nakamura Mirror self-recognition in non-human primates: a phylogenetic approach Jpn. Psychol. Res., 39 (1997), pp. 266–275

- S. Itakura Use of a mirror to direct their responses in Japanese monkeys (Macaca fuscata fuscata) Primates, 28 (1987), pp. 343–352

- V.A. Kuhlmeier, S.T. Boysen, K.M. Mukobi Scale model comprehension by chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) J. Comp. Psychol., 113 (1999), pp. 396–402

- V.A. Kuhlmeier, S.T. Boysen The effect of response contingencies on chimpanzee scale model task performance J. Comp. Psychol., 115 (2001), pp. 300–306

- V.A. Kuhlmeier, S.T. Boysen Chimpanzees’ recognition of the spatial and object similarities between a scale model and its referent Psychol. Sci., 13 (2002), pp. 60–63

- L.E. Law, A.J. Lock Do gorillas recognize themselves on television? S.T. Parker, R.W. Mitchell, M.L. Boccia (Eds.), Self-awareness in Animals and Humans: Developmental Perspectives, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1994), pp. 308–312

- A.C. Lin, K.A. Bard, J.R. Anderson Development of self-recognition in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) J. Comp. Psychol., 106 (1992), pp. 120–127

- L. Marino, D. Reiss, G.G. Gallup Mirror self-recognition in bottlenose dolphins: implications for comparative investigations of highly dissimilar species S.T. Parker, R.W. Mitchell, M.L. Boccia (Eds.), Self-awareness in Animals and Humans: Developmental Perspectives, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1994), pp. 380–391

- T. Matsuzawa The visual world of a chimpanzee University of Tokyo Press, Tokyo (1991) (in Japanese)

- T. Matuzawa The Ai project: historical and ecological contexts Anim. Cogn., 6 (2003), pp. 199–211

- E.W. Menzel, D. Premack, G. Woodruff Map reading by chimpanzees Folia Primatol., 29 (1978), pp. 241–249

- E.W. Menzel, E.S. Savage-Rumbaugh, J. Lawson Chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) spatial problem soling with the use of mirrors and televised equivalents of mirrors J. Comp. Psychol., 99 (1985), pp. 211–217

- M. Miyazaki, K. Hiraki Delayed intermodal contingency affects young children's recognition their current self Child Dev., 77 (2006), pp. 736–750

- S.R. Poss, P. Rochat Referential understanding of videos in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes), orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus), and children (Homo sapiens) J. Comp. Psychol., 117 (2003), pp. 420–428

- D.J. Povinelli Failure to find self-recognition in Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) in contrast to their use of mirror cues to discover hidden food J. Comp. Psychol., 103 (1989), pp. 122–131

- D.J. Povinelli, A.B. Rulf, K.R. Landau, D.T. Bierschwale Self-recognition in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes): distribution, ontogeny, and patterns of emergence J. Comp. Psychol., 107 (1993), pp. 347–372

- E.S. Savage-Rumbaugh Ape Language: From Conditioned Response to Symbol Columbia University Press, New York (1984)

- K.B. Swartz, S. Evans Not all chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) show self-recognition Primates, 32 (1991), pp. 483–496

Keywords

Chimpanzee, Self-recognition, Live-video image,